For centuries a bat has stood proudly above Valencia’s coat of arms. A curious animal to choose for such a prominent position, one would think. So why does Valencia’s bat matter so much? And did it really play a decisive part in one of the main turning points of Valencian history?

The Valencians love their bat, at least symbolically! Football teams, street furniture, public buildings, the Fallas cultural associations, and even business logos feature this black, furry, winged animal. Funnily enough though, they cannot seem to agree on its name. In all the territories speaking variants of Catalan, Balearic, or Valencian, more than eighty names are in use. Variants include blind mouse, devil’s bird, winged rat, flying rat, night’s bird, or simply the outdated scientific name, vespertilio.1

There is even a lexicographical discussion around the exact meaning of the most-used name in Valencian, rat penat. Does it mean ‘hanged rat’ or ‘punished rat’ in the sense of a criminal hanged from the gallows for his crimes? Penar in Valencian means ‘to penalise’ and after all bats hang from ceilings while at rest. Or should you read it as ‘winged rat’? Penat could originate from the Latin pennatus, meaning ‘feathered.’ My guess is as good as yours.

In any case, this threatened species contributes actively to Valencia’s liveability. A small bat can eat up to one thousand mosquitos per hour. Very effective pest-control for farmers, and a blessing for us in summer! Yet this is probably not the reason a bat crowns the Valencian coat of arms. For that, we must travel back in time.

Batty legends

Look around on the internet a while, or listen to some guides on the streets of Valencia, and you will hear a host of stories explaining the origin of Valencia’s bat. Most of them trace the blind mouse back to king Jaime I of Aragón’s crusader siege of Valencia in 1238. Details on the how, why, where, and even when can differ, but usually a bat somehow saves Jaime’s life from an attack by a Muslim army.

Saved by the b… bat

One story has a bat waking Jaime up at night to warn him of an impending attack by Valencia’s defenders. This allowed Jaime to wake up his soldiers just in time, turning a supposed surprise attack by the Muslims into a victory for the crusaders. Others instead assert that the surprise attack worked, but that a bat saved Jaime in the ensuing battle. La Fallera Calavera, a satiric story based on a popular Valencian card game, recounts a variant of this story:

Great was my surprise when, waking up, I saw my camp in flames. Horrific cries and heavy smoke had alerted me. My soldiers were almost all dead or burned. […] Right when I wanted to react, Zayyan appeared in my tent. Carrying a great axe, he began to attack me and was about to cut off a leg. Never in my life was I more afraid than that day. And when I already thought that all was lost and the Saracen leader would run me through, an animal appeared that would be my salvation. It was a bat that, flying around Zayyan’s head, distracted my enemy. Without sword nor soldiers I could do nothing more than flee. I started to run until I got far away from the city, sad and downcast.

Chapter 5, “La llegenda de l’orxata”, in La Fallera Calavera, by Enric Aguilar. (Translated by the author).

Of course, in this telling, Jaime then finds a woman who offers him a mysterious potion – horchata – which takes him back in time to the evening before the attack so that he can prevent this disastrous turn of events!

True story, but fake news

An often-repeated story tells how at some point during the crusade for Valencia, Jaime encountered a bat in his tent. This flying rat took up residence in the nook of the royal pavilion. Against all reason, it did not bother Jaime. What is more, when it was time to move camp, he ordered that his tent should not be broken down until the bat would leave of its own volition. And something like this truly happened! We know this from Jaime himself, from his ‘autobiography’ El Llibre dels Fets:

When I was at Burriana [in 1237] we broke up camp, but a swallow had made a nest in my tent, and I ordered that the tent should not be removed until the bird and her chicks left it, because it had placed its confidence in me.

El Llibre dels Fets, by Jaime I of Aragón. (Translated by the author).

So yeah, it turns out to be a bird rather than a bat. It is an important moment for Jaime nonetheless – we know, because he cared to include this small episode in his memories. I think he shared this to symbolise his benevolence and trustworthiness as monarch: “Trust me, I am a good king and will take care of you as well!” The supporters of this tale should probably petition the Valencian city council to change the bat to a swallow…

Expand: The bat and the swallow

Interestingly, Spanish folklore has another story featuring both a bat and a swallow. The tale comes from Garrotxa in Catalonia. The story is about a contest between God and the devil about who can make the most beautiful bird. God ends up creating a swallow, while the devil creates a bat…

Sym-bat-logy!

A lot of tales have Jaime give a symbolic meaning to the bat, whatever the circumstances of its appearance. One claims that the bat was a pet of Zayyan, the Moorish king of Valencia. One day it escaped and flew away to Jaime’s tent, attracted by the bright reflection of Jaime’s helmet. I suppose this implied God’s favour turning from the Muslims to the Christians, leading the former to open negotiations to surrender the city.

A book published in 1588 builds on the story told earlier, where a bat nests in Jaime’s tent – in this case supposedly the royal pavilion at Ruzafa. The author claims Jaime saw this as a portent of his victory over Valencia. Thus, on 9 October 1238, the day of his triumphal entry into the city, he had a bat placed on top of the royal standard.

The General Chronicle of Spain, written in 1604, says that “the king took [the bat] as his emblem to show that it was more through cunning than by force that one takes and conquers a kingdom such as Valencia.” The Annals of the Kingdom of Valencia, published nine years later, had a slightly different take:

On the banner was the royal coat of arms, and on these the king ordered placed as a crest a bat, which in Valencian2 is called rat penat. And so the banner with the royal coat of arms was placed on the tower to signal the victory that the king had achieved over the city and its Mores, who walk in the darkness of the sect of Mohammed, which is signified by the bat, a nocturnal animal, which cannot and knows not how to escape from the darkness. It can be presumed that the king placed the bat in his coat of arms as a trophy of the conquest of Valencia.

Annals of the Kingdom of Valencia, by Diago. (Translated by the author).

Again, all these different stories we can safely discount as later inventions, thanks to El Llibre dels Fets. Jaime never wrote about any such happenings, which we might expect if it truly happened. Strong symbols celebrating the king’s ability, achievements, and victory over the Muslims would have fit right up his alley in presenting himself as God’s champion. But he recorded nothing of the kind!

Finding Valencia’s bat

To find the true origin of the bat, we are going to move backwards in time. I am relying mostly on two sources. One is a monograph written by Vicente Vives y Liern in 1900: Lo Rat Penat en el Escudo de Armas de Valencia. He tries to find the origin of the bat and to argue why it remains important as a Valencian symbol. The other source is an exposition in the Palau de Cervelló, running until 1 September 2024. La evolución del escudo de la ciudad de Valencia en imágenes shows all the modifications the city’s symbols have gone through since 1238.

Valencia’s bat in modern times

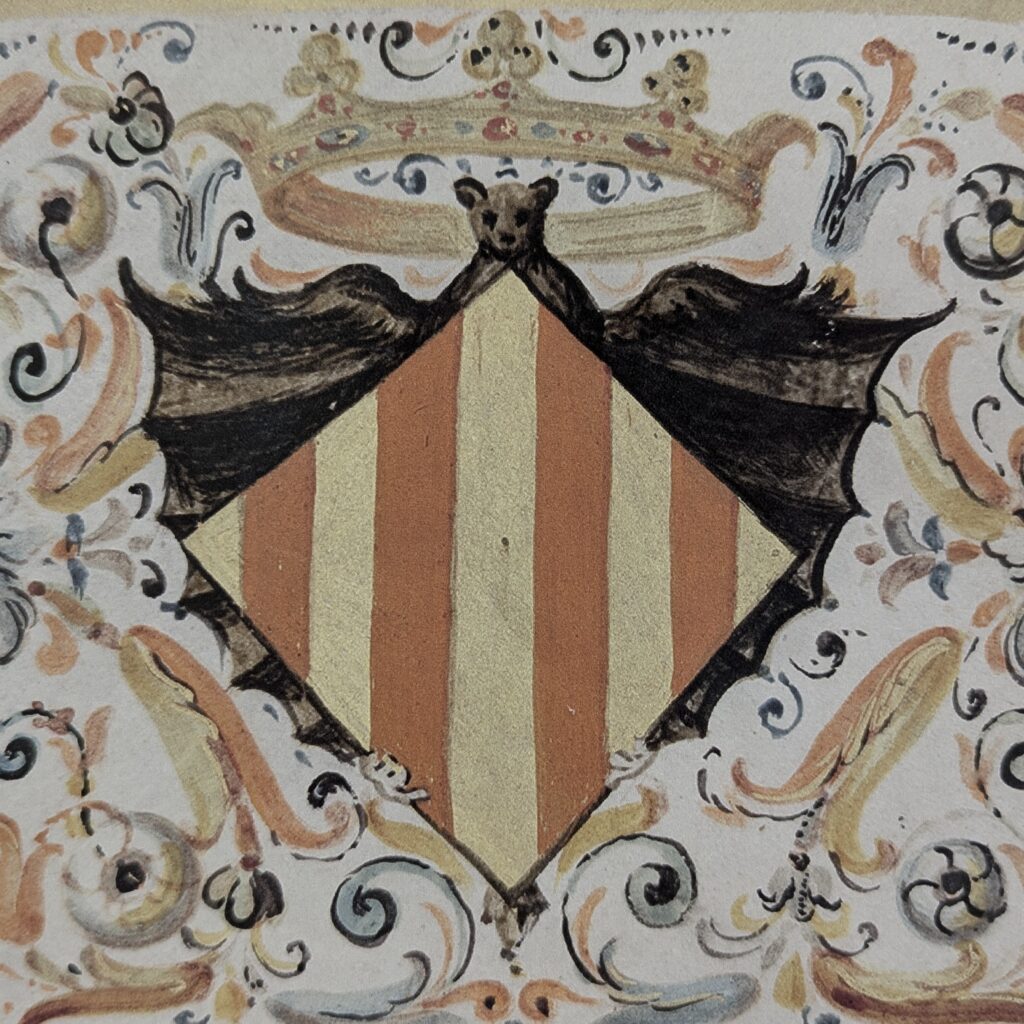

The current coat of arms of the city council (the one shown here) has been in use since 1987. But you can recognise the same elements all the way back to the 1600s. In the centre stands a diamond shape, with four vertical bars across it. Above it you see a crown, and above that our lovely bat! On the sides stand two Ls with little crowns above each. Often laurels curve up on either side.

However, Valencia’s bat slowly starts disappearing if we move back beyond 1600. The earliest visual representation of the bat I have found (and please, let me know if you find an earlier one!) comes from 1585. The animal spreads its wings over the diamond-shaped coat of arms of Valencia, with a crown above it. It is a highly elaborated art-piece, included in a book claimed to be a papal bull of pope Sixtus V. Strangely, I cannot find any further information about the context of this papal bull, or why Valencia’s coat of arms would be in it.

But something strange is going on. Even though there is no visual proof of any bats in Valencian heraldry before 1585, literary sources keep mentioning bats in this context much further back, at least as early as 1448! How is that possible?

Good old confusing language: what is a rat penat?

In 1448, during the construction of the Torres de Quart city-gate, a document claimed that a payment was made to a painter “for designing and painting two bats as a sample for the purpose of making some of marble for the Quart gate.” Similarly, when the City Council orders a new banner made in 1503, they “approve that the treasurer gives to the merchant Jacme Climent twelve ducats for making the crest and bat of the new flag that the city has now made.”

But when we look at the medieval flag of Valencia, or at the coat of arms on the Torres de Quart (or the Torres de Serranos, for that matter), there is no bat to be found! Instead, a dragon stands above both. And here is a clue to the origin of the bat: in medieval times – at least between 1448 and 1503 – the Valencian words rat penat referred not only to a bat, but also to a dragon… The ‘dragon’ definition eventually fell out of use, while the ‘bat’ one stuck around, leading to later confusion.

Here be dragons

But why would a dragon be shown on the Torres de Quart in 1448? Because in that year Valencia’s coat of arms did not include a dragon. The answer: it showed who Valencia was loyal to. The city-gates were the first public buildings a visitor would see up close. Walking in under its arch and looking up, they would see the coat of arms of the king of Aragón, Valencia’s liege lord. And at that time the Aragonese royal coat of arms boasted a dragon.

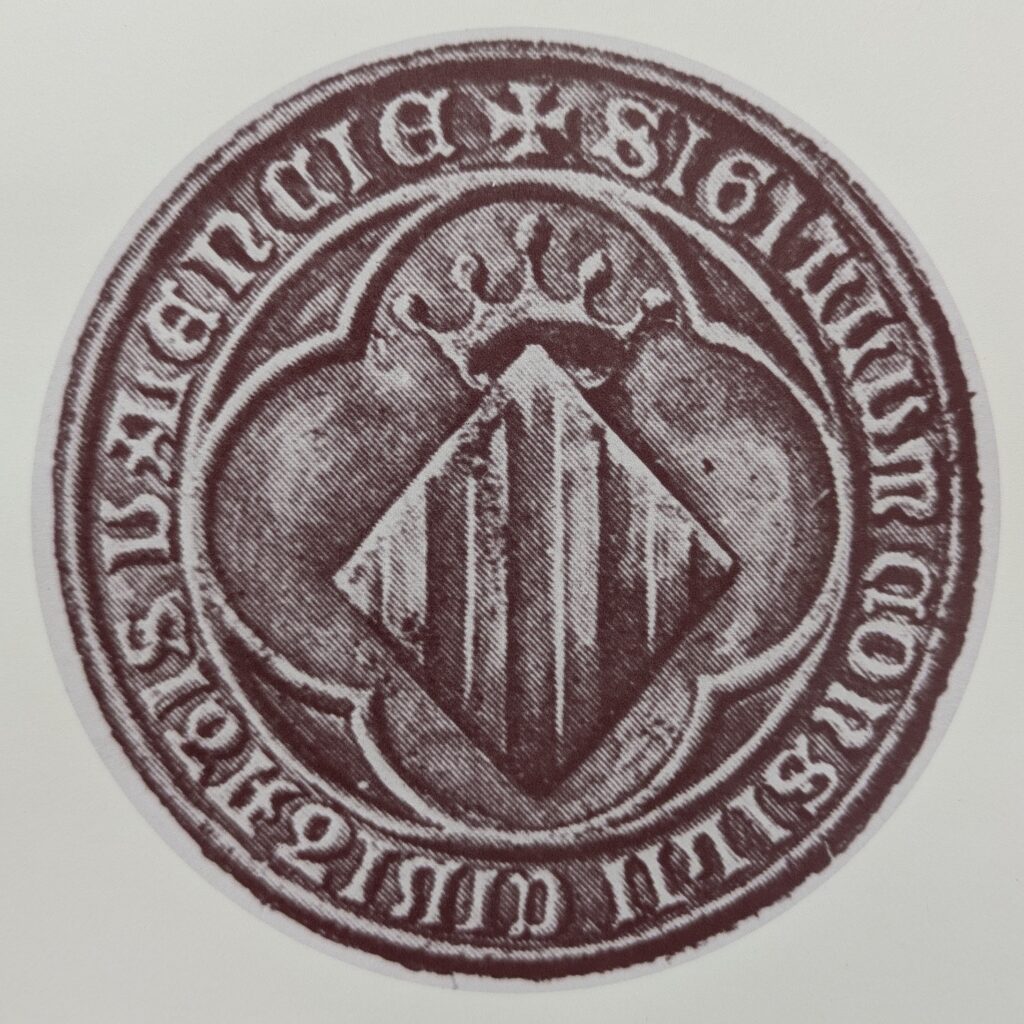

Thus, before 1500 the dragon was not a part of the city’s coat of arms, but of the king’s. In fact, the Valencian coat of arms was rather simpler: a golden or yellow diamond shape, with four vertical red bars across it, and only a crown above it. This version existed since 1377, and the city council neatly explained why the crown was there, without mentioning any bat or dragon:

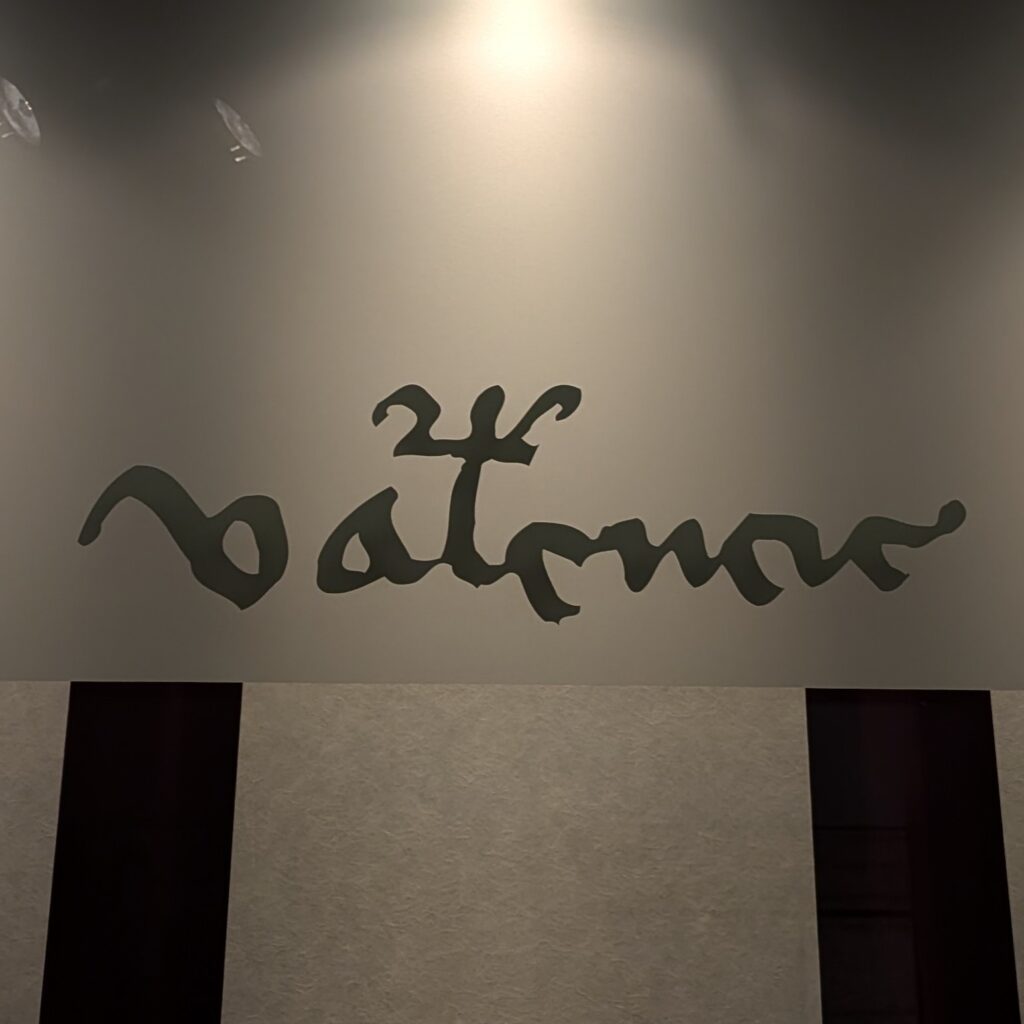

…on top a crown is added, for two reasons: the first, because this city is the capital of the Majority Kingdom;3 and second, because the highly esteemed, currently reigning king – on his own accord and out of mere generosity – deems that the seriousness of this city shown in the recent war with Castilla,4 especially during the two sieges and principally in the second suffered by the city at the hands of the king of Castilla, merits adding this crown to this seal, and for higher certification and remembrance this king, for now and ever, when signing royal letters by his own hand, on his title where it says “King of Aragon, Valencia, etc.” on the ‘L’ which appears in the middle of the name Valencia, paints a crown by his own hand, thus forming VaΨencia.

As quoted by Vicente Vives y Lierns, p. 37-38. (Translated by the author).

Just after 1500, the Valencian city council updated their logo again: a dragon was now included above the crown. One theory holds that around that time, heraldic fashion suddenly became to include crowns in everything. Consequently, it was no longer a sign of special royal status or preference – as was the case with Valencia – but merely a fashionable element. How then to show that Valencia truly stood apart from ‘regular’ cities? The city council decided to adopt the king’s dragon to make sure people kept associating Valencia with the king!

Towards the modern bat and dragon

Around the same time however, the royal house of Aragón fused with the royal house of Castilla, and the dragon slowly fell out of use in the royal coat of arms. That left the dragon to Valencia! Confusion regarding the definition of the words rat penat, combined with non-standardised depictions of the coat of arms, lead the city’s dragon to slowly morph into a bat over the 16th and early 17th century. For decades books, buildings, and seals used dragons and bats interchangeably, or sometimes even simultaneously! The bat was officially adopted in 1633 by the city council, starting the coat of arms’ evolution to our current symbol.

In the 19th century the government created the administrative division of the Province of Valencia. This new territory adopted a logo which historically represented Valencia far beyond the city walls: the royal coat of arms of the old kingdom, dragon included. And just last century, the new regional government – the Generalitat Valenciana – also chose that same symbol. For the Generalitat it was even more appropriate: the territory it governs maps almost perfectly with the old kingdom of Valencia. Thus, both the dragon and the bat survive to our times, thanks to different Valencian institutions.

Valencia’s bat, dragon, and conqueror

As we have seen earlier, Valencia’s bat is heavily associated with king Jaime I of Aragón. We have seen that the bat originated as a dragon. But does the dragon have anything to do with Jaime? And no, unfortunately it does not. The dragon did not exist in Jaime’s time. When he was king, the royal coat of arms was simply a yellow shield with four vertical red bars. Nothing more, nothing less. The dragon came along with Jaime’s great-great-great-grandchild: king Pedro IV.

Around 1337-1343 king Pedro IV of Aragón adopted a new heraldic fashion: including mythical beasts. Above his family’s coat of arms he placed a helmet and a dragon. Why a dragon? We do not know for certain. Some think it had to do with the patron saint of Aragón, Saint George the Dragonslayer. Others think it is a play on words: rei d’Aragó (king of Aragón) sounds similar to rei dragó (dragon king)!

This dismisses the popular image of king Jaime I the Conqueror, depicting him with a beautiful winged dragon-helmet. You can still find this helmet on a bust in the town-hall of Valencia (seen on the picture just above), and on the statue on Plaça d’Alfons el Magnànim. It looks awesome, but is unfortunately ahistorical.

Conclusion

So what are we to make of this? Well, first of all, that Valencians have an amazing imagination! A whole spectrum of beautiful tales, each more spectacular than the last one, are all based on an etymological mistake. Rat penat might have meant ‘bat’ for centuries already, but at a particular time in a particular place meant ‘dragon’ instead.

How do you explain that ‘bat’ and ‘dragon’ were the same word? I do not have a definite answer to that, but I imagine it has to do with the wings. Dragons are usually depicted with wings closely resembling those of a bat. With no other real-life equivalent to compare it to, why not call it a ‘bat’ when you gave an artist the assignment to design a dragon-crest? Everyone knew that the coat of arms carried a dragon, right? Right…?

All this does not mean that the bat should lose its meaning for Valencians. It still represents them, both culturally through for example the Fallas and city symbols, as during their football games. For more than four hundred years the bat has been present in Valencia. And the very existence of all these stories surrounding the devil’s bird proves that the Valencians care for it!

Moreover, folklore and myths, whether accurate or not, still make up part of a place’s culture. Imagine talking about ancient Greece while ignoring all the myths about Zeus, Athena, and Poseidon and their exploits because they are clearly fictional… No, instead you include these stories as well, because they tell you something about what the ancient Greeks though was important. And so talking about Valencia’s bat – and its dragon – you find out what the Valencians care about: their founding father, king Jaime I the Conqueror, and his victory over Muslim Balansiya in 1238, as well as Valencia’s status in Jaime’s kingdom!

Next time, we will find out what actually happened during the siege of Valencia: if there was no bat to bother king Jaime, how did he manage to conquer the city?

Sources

- A Search for the Hidden King: Messianism, Prophecies and Royal Epiphanies of the Kings of Aragon (circa 1250-1520), by Amadeo Serra Desfilis.

- La Fallera Calavera, by Enric Aguilar.

- Llibre dels Fets: la conquesta de València, by Jaime I.

- Lo Rat Penat en el Escudo de Armas de Valencia, by Vicente Vives y Liern.

- Los murciélagos de la biblioteca de Galdós. La gestación de las ciencias de la psique en el siglo XIX y los emblemas personales de Galdós como documentos simbólicos, para su psicoanálisis, by Alejandro García Medina.

- Los nombres del murciélago en el dominio catalán, by M. Sanchís Guarner.

- Los ratones voladores, by Jesús Monedero Ramos.

- Exposition: La evolución del escudo de armas de la ciudad de Valencia en imágenes, by the Archivo Histórico Municipal de Valencia.

- El señal del rey de Aragón: historia y significado, by Alberto Montaner Frutos.

- La Senyera Valenciana: Historia y simbolismo, by Òscar Rueda.

- Commemorating a Providential Conquest in Valencia: The 9 October Feast, by Francesc Granell Sales.

Footnotes

- Respectively, moriciego/muixirec (along with a dozen variations), aucell del dimoni, rat penat, rat-volant, aucell de nit, and vespertilio. For a full discussion of all 81 names, read ‘Los nombres del murciélago en el dominio catalán,’ by M. Sanchís Guarner. ↩︎

- The original text says “en Lemosin,” a medieval name for the same language. ↩︎

- Meaning that the Kingdom of Valencia was at that time (claimed to be) the most powerful kingdom in the Crown of Aragón (which also included among others the old Kingdom of Aragón itself, and the County of Catalonia/Barcelona). ↩︎

- The War of the Two Peters: a thirteen year-long conflict between king Pedro I of Castille and king Pedro IV of Aragón, in which Valencia was besieged two times but never surrendered. ↩︎