When the Romans arrived on the Iberian Peninsula, they did not encounter an empty plot of land. From the Pyrenees all the way south to nowadays Andalusia, Iberian tribes had carved out territories for themselves. One of these was Edeta, a city-state on par with those of the ancient Greeks. So who were the Edetani, the people who built a civilisation centuries before Valencia came into being?

A big town with lots of water

Edeta went under two names, both originating in the Iberian language. Edeta means “Plenty of water” and was the town’s original moniker. The second name is Llíria. As evident from its meaning, “Big town,” it probably came much later when Edeta had grown to a significant size.

The town of Edeta stood on the Tossal de Sant Miquel, a hill on the southern edge of the modern city of Llíria. Climbing this hill, you immediately understand why the Edetani built their homes here. A beautiful – and useful, in ancient times – view stretches out in all directions. Far to the east, the skyline of Valencia rises in front of the Mediterranean Sea. Five kilometres to the south the Turia river winds its way through the valley. Westwards small hills slowly start to appear as the terrain gets rougher. And to the north, the mountains of the Serra Calderona mark a natural border.

From Edeta to Edetania

The immediate neighbours of Edeta were the towns of Arse (nowadays Sagunt) and Sucro (nowadays Albalat de la Ribera). Both towns were also ethnically Edetani. The whole territory where this tribe lived – Edetania – stretched from the Millars or Mijares river in the north to the Xúquer or Sucro river in the south.

Though ethnically uniform, Edetania was not a single political unit. Arse, Sucro, and Edeta all fended for themselves. Yet there were extensive road networks between them, evidence of active trade – and probably social connections!

Getting to know the Edetani

Edeta’s growth kicked off around 550 BCE. While the warrior elite lived on the strategic hilltop itself, villages and farms started to appear on the flatlands north-west of the town. Over the next 350 years more than fifty settlements popped up, each servicing the town in some way. Farmers supplied Edeta with cereals, grapes, wine, and olives. Some villages specialised in mining iron and metallurgy, key Iberian skills. On strategic hills fifteen watchtowers provided security. The ‘knights’ who lived here also hunted wild animals for additional food. Most of these little ‘castles’ stood north of the city, guarding the entryways into the Serra Calderona mountains.

A curious fact about the Iberians: they adopted writing quite early on, often using alphabets from foreign traders, such as the Greeks and Phoenicians. Reading that made me excited to find out what the Iberians – and our Edetani – wrote about! But my excitement was short-lived. Turns out, the Iberian language has not yet been deciphered. So while we know exactly how the Iberian language was written and how it sounded, we have no clue what those sounds actually meant…

Nevertheless, we fortunately still know quite a lot about how the Edetani lived. Some of that knowledge is deduced from the wider Iberian culture, while other information comes straight from the Valencian earth. So let us find out what the Edetani people did with their lives!

What work did they do?

We start with our Edetani farmers. Many of them worked with cereals, a basic produce for most societies. We know that Iberians made beer with those cereals at least since the second millennium BCE, so it is safe – and pleasant! – to assume that you could get a nice ale in Edeta after a long day in the sun. If you are more of a wine-person, you could also get your fill! Iberian wine was good enough that the Phoenicians traded it internationally. The Edetani furthermore grew olives and other fruits, using trees that required little to no irrigation, and they practised beekeeping.

The Iron Age

Iberian society became famous for working with iron, and Edeta was no exception. When the Phoenicians first arrived on the Iberian Peninsula, they introduced iron metallurgy. This new technology created stronger tools, making labour more efficient, and so allowed people to specialise beyond just agriculture and hunting. In the end, this made Edeta’s growth into a small city state possible: a hierarchical society where farmers, hunters, miners, and artisans provided the essentials, while the warrior elite secured the territory’s borders and went to war when necessary.

Incidentally, the Edetani metal-workers did not just make tools, but also jewellery. Throughout Edetania various examples were found of bronze pendants in different shapes, including animals. Of course, the suggestion is often that such pendants were religious in some way, but there is always a chance that it was just art: a shape or animal that pleased its wearer!

Traders

What could not be created locally, arrived by overseas trade. Edeta was located a bit too far inland to profit directly from trading, but its neighbour Arse (Sagunt) benefitted enormously. Its location on a hill a stone’s throw away from the beach made it the perfect trading post for Edetania. Arse was, probably due to that trade, the first Edetani settlement to mint its own coin!

The Edetani elite

For those too rich and powerful to dirty their hands with regular work, other activities had to be arranged. Of course, being powerful, the men had the responsibility to fight when duty called. It seems that Edetani men were thrill-seekers: in peacetime they went hunting, or tried taming horses and bulls.

Fragments of decorated pottery show ritual dances, as well as women on thrones. Given the misogyny of the past, this probably does not point towards women exercising political power. Excluding that, I imagine that women took up roles in religious or cultural ceremonies. A 2.500-year-old precedent for the Fallera Mayor, maybe?

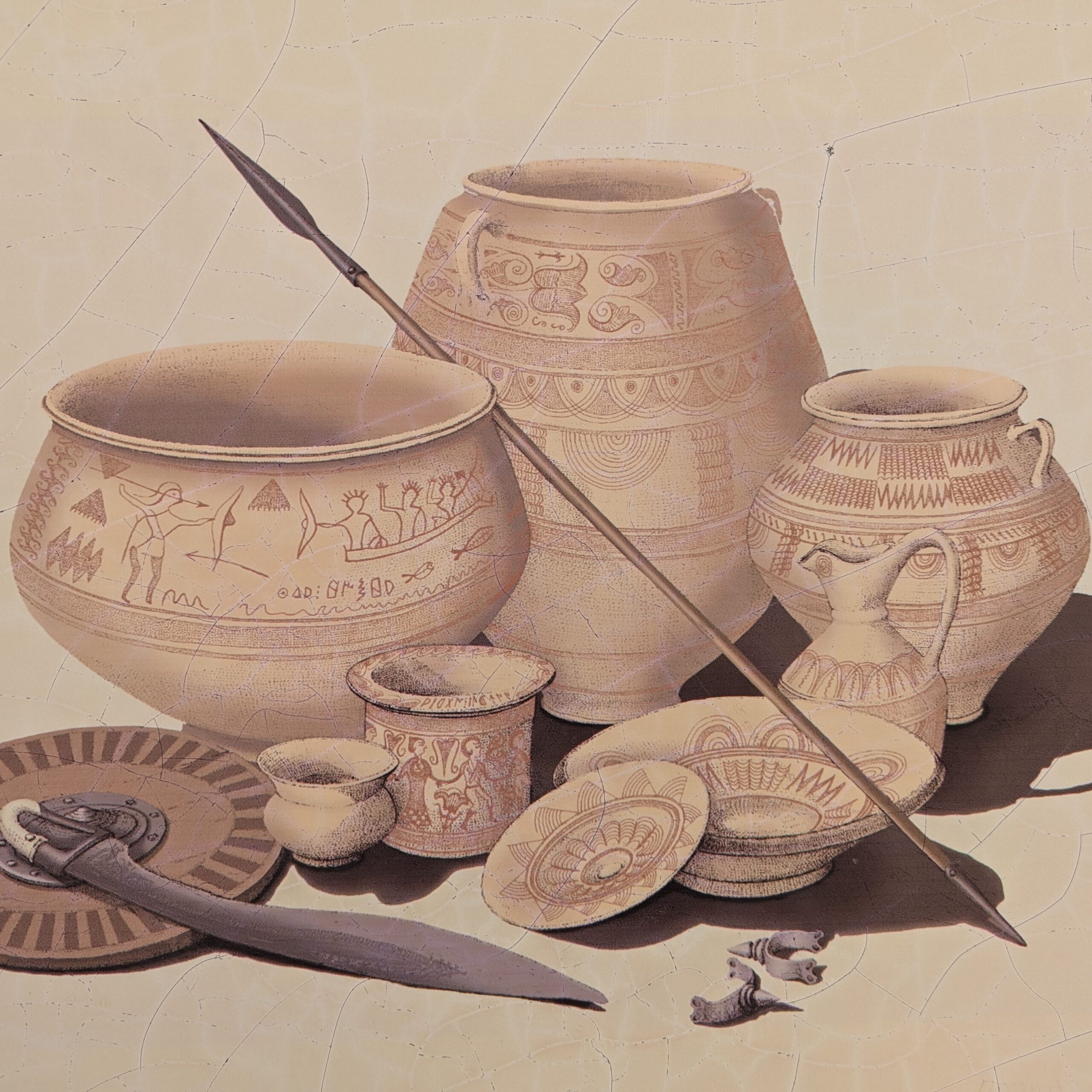

Edeta’s ceramic artistry

The Edetani did not make a lot of sculptures (that was more of a Contestani forte, the people of nowadays Xàtiva), but they did excel in pottery. Regular Iberian pottery used to be of a darker colour and decorated with pictures of animals and some plants. Edeta stood out with ceramics with an off-white colour, and decorated with geometric patterns. This remained popular in the area long after Roman Valentia took over Edeta’s prominent position!

Interestingly, in the larger settlements of Edetania, archaeologists often found another type of ceramic decorations. These were not (completely) designed with geometric patterns, but with humanoid figures instead, showing war scenes, the earlier-mentioned woman on a throne, or even mythical beings. Experts suspect that these designs were commissioned by rich people leading those settlements – they often showed cultural aspects exclusively accessible to the elite.

Death in Edeta

In life, death is a given, and so the Edetani also had their ways of dealing with the end. They would cremate the deceased and bury them in urns, but different to us, it was not the ash they kept, but the skull and the larger bones. After having burned the body, the bones were separated from the other remains and ashes. They washed these, placed them in an urn – the more richly decorated, the richer the person within it – and then buried that in a necropolis.

A rather gloomy detail concerns those who died prenatally. In the – really quite small – excavated area of Edeta, archaeologists found five foetuses buried below the floors of houses. It seems the Edetani kept children who died before they were even born very close-by. Whether this was a place of love and remembrance, or rather a way to avoid public embarrassment, is not entirely clear…

A final curious fact regards the death of dogs and horses. The remains of dogs, for being such a ubiquitous animal, have rarely been found in ‘regular’ places, such as at farms or close to houses. Rather, they turn up almost always in ritual or sacred spaces. In a few cases these areas also featured the bodies of horses. Experts suspect that these animals – that often are very dear to their owners – were either ritually sacrificed to the gods, or received a special, sacred burial after they died.

The fall of Edeta

And so life went on for centuries – with the natural ups and downs that life brings with it, yet overall Edetania remained stable. Especially from 400 BCE onwards the population grew rapidly, and the cities’ governments grew along with them. At this time, the average territory dominated by a city in the current Valencian Community was between 800 and 1.700 square kilometres. That is comparable with contemporary Greek city-states!1

The Second Punic War

Yet right when all went well, the Second Punic War brought calamity to Edetania. Carthage, a powerful city in nowadays Tunisia, had expanded into Iberia, right onto the doorstep of Edetania. The other Mediterranean powerhouse, Rome, felt threatened by Carthage’s expansion. Edeta had a front-row seat when the Carthaginian general Hannibal attacked its neighbour Arse, which the Romans called Saguntum. Arse-Saguntum had made a pact with Rome that the latter would protect the former. And so began sixteen years of warfare in Iberia.

Edeta, sadly, did not stand with its Saguntine brothers, though likely that is how they avoided the destruction of their own city. What is more, we know that some years later, Edeta fought for Hannibal, rather than against him. This was not necessarily because they liked the man, but because they were forced. The Carthaginians had taken the families of important Iberian leaders hostage, including that of the king of Edeta, Edeco.

It is safe to assume that Edeta witnessed a lot of the war. Five years into the conflict, the Romans reconquered Arse-Saguntum. For a while they dominated the area of Edetania. If Edeta at this time was truly providing soldiers to Hannibal’s cause, we can imagine that the Romans did not take kindly to them…

Edeco’s salvation

The year 209 BCE marked a turning point, however. At that time, Edeta was probably at the zenith of its power. Archaeologists estimate that the town now occupied some ten hectares, about as much as Valentia would measure a century later. Its ruler, Edeco, the only Edetani chief mentioned by name in our sources, was seen as one of the most prestigious Iberian leaders at the time.

In that year, Roman commander Scipio mounted a surprise attack on Cartagena,2 the main Carthaginian city in Hispania. After taking the town, Scipio found a large group of hostages, taken by Carthage from prestigious Iberian families. As soon as Edeco of Edeta heard that his family too had fallen in Scipio’s hands, he deserted and offered his allegiance to the Roman general. Due to his high social standing, many Iberian warlords soon followed his example, and suddenly the balance of power shifted. The days of Carthage in Iberia soon came to an end.

So much for Roman gratefulness…

That left Iberia and Edetania firmly within the Roman sphere of influence. Rome soon established provinces in Hispania. This new legal framework, enforced by a Roman army, stripped away Edeta’s autonomy. To prevent rebellions from strong defensive positions, the Romans forced many tribes to abandon their hilltop fortresses and towns, and to resettle in unfortified settlements on lower ground. Edeta, just a few decades before at its most powerful, was razed to the ground. The Edetani abandoned their hill, and built new houses 500 metres to the north-east. ‘Modern’ Llíria’s old town still lies there, looking up to the summit of its ancient origins…

Conclusion

Ancient Edeta fascinates me. Of course, when talking about Valencia we tend to look at its own Roman origins. However, Valentia Edetanorum was not founded in a vacuum. The clue is right there in the epithet Edetanorum: “of the Edetani.” The town might physically have been new, yet it colonised a territory which had already seen a socially complex, literate, and culturally rich society rise and fall over the course of many centuries. The Romans should not get credit for creating Valencian society – they conquered it, and then forced it to assimilate. Edeta was here long before the Romans came.

Sources

- El Tossal de Sant Miquel de Llíria: la antigua Edeta y su territorio, by Helena Bonet Rosado.

- From the archaic states to romanization: a historical and evolutionary perspective on the Iberians, by Joan Sanmartí.

- Historia de la Hispania romana, by Pedro Barceló & Juan José Ferrer Maestro.

- Interpreting protohistoric societies through place names of landscape features: a case study in València, Spain, by Joan Carles Membrado-Tena.

- La fundación de Valentia y los territorios ibéricos circundantes, by Consuelo Mata Parreño.

- Reflexiones sobre la organización territorial en el país valenciano entre los siglos VI y II a.C., by Helena Bonet Rosado & Jaime Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez.

- Saetabis versus Edeta, Saguntum, Valentia y Carthago: interacción y dinamismo en el Levante hispánico, by María Amparo Bellvís Giner.

- The substratum permanent structures of Roman Valencia, by Giancarlo Cataldi & Vicente Mas Llorens.

Footnotes

- Not quite as big as the famous Athens (Attica covered 2550 square kilometres) or Sparta (even bigger), but also much larger than the majority of city-states in ancient Greece (80% of the ancient Greek poleis ruled 200 or fewer square kilometres). So Edeta would have counted as a medium-to-large city-state to contemporary Greek observers. See ‘The Physical Parameters of Athenian Democracy,’ by D.M. Pritchard. ↩︎

- Cartagena is derived from Carthago Nova, which means New Carthage. That is actually a Roman name, as the Carthaginians had simply called it Carthage (or technically “Qart Hadasht“), exactly the same as their city of origin. Not confusing at all! ↩︎