As Valencia’s oldest market, the Mercat Central deserves its place among the city’s array of monuments. Its design is astounding, taking cues from famous markets such as Les Halles and Mercat del Born, and combining these with an homage to Valencian produce and products. But have you ever noticed it also resembles a medieval church?

A millennial market

The Mercat Central takes the cake for being Valencia’s oldest marketspace still in use today, of the seventeen markets spread out throughout the city. Its history dates to Al-Andalus, when local farmers came to this small plain – then just outside the city’s walls – to sell their produce. After conquering Valencia in 1238, King Jaume I formalised the market through a royal privilege. When the city expanded, it left the market’s area as one of the few open spaces within Valencia-city.

In the 19th century, along with many other cities, Valencia needed a larger, modern market. As the city grew, demand increased and local farmers selling their produce could no longer satisfy it. Interregional and international trade provided the needed products, but also required a better distribution system.

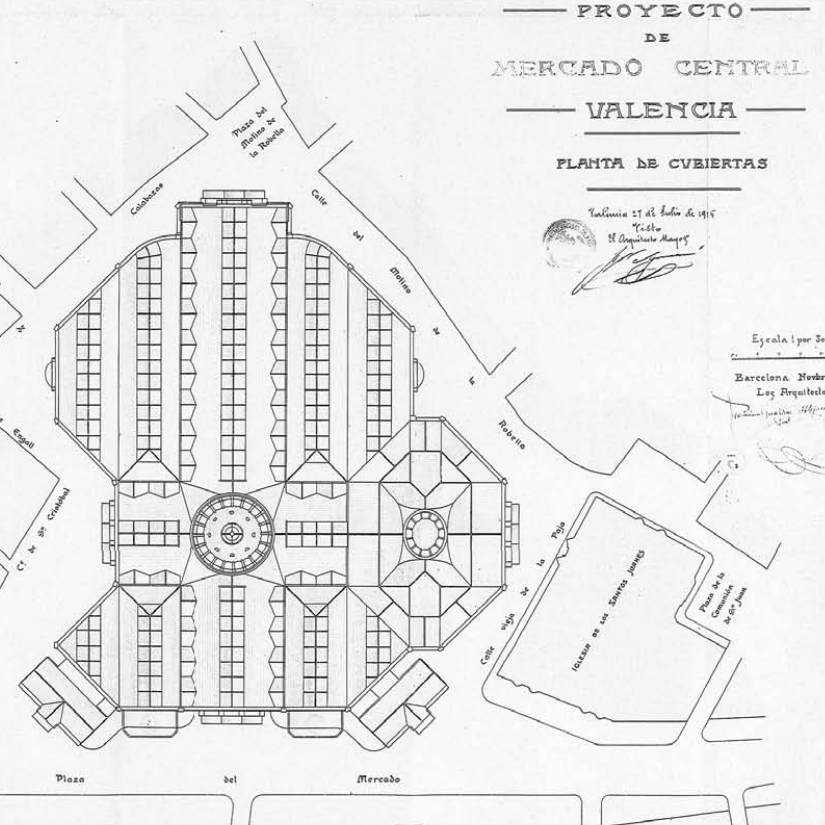

An early attempt, the Mercado Nuevo, proved inadequate, and so in 1910 a tender went out for a new market. The project proposed by Catalan architects Alexandre Soler i March and Francesc Guàrdia i Vial won. The Mercat Central de València’s construction lasted from late 1915 until early 1928. Despite the long and arduous process, it resulted in one of Valencia’s most beautiful and unique monuments!

Churchly language

With its long commercial history in mind, it is curious to note how often descriptions of the Mercat Central evoke images of religious sanctuaries. It begins already with the market’s own website, which proudly proclaims itself to be “The Cathedral of the Senses”. A beautiful description, calling to mind the blend of colours and aromas pervading its passages. Writer Joan Francesc Mira uses similar words to laud the Mercat Central de València’s structural attributes:

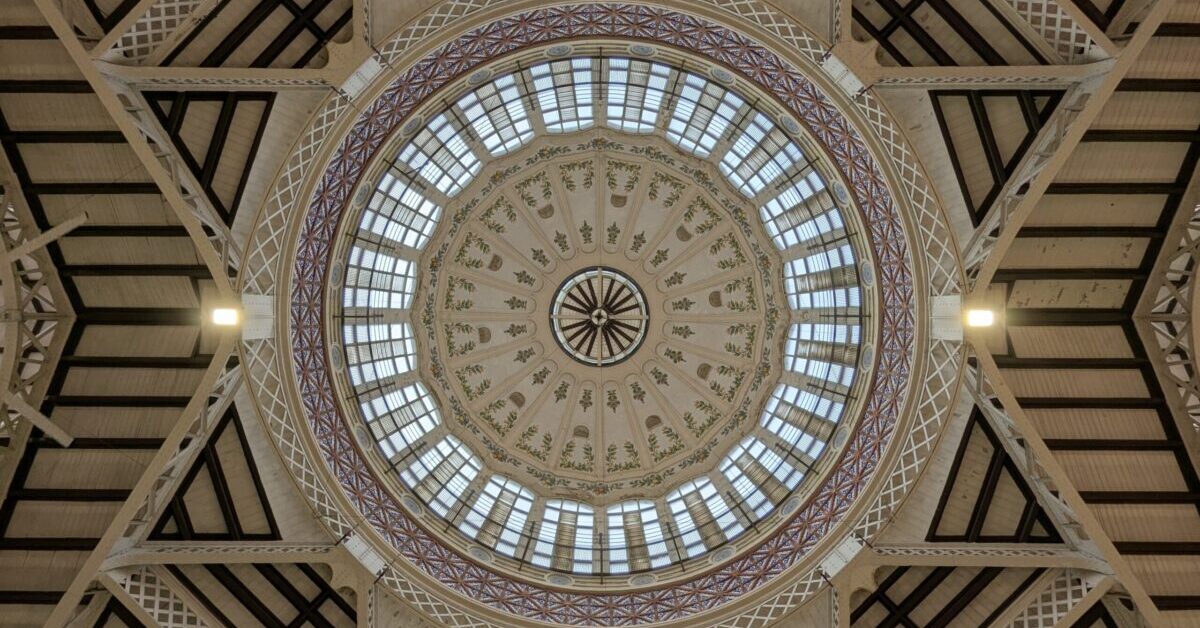

We continue to the market, then, which is not just any other market: it is an enormous building, like a vast and dazzling cathedral, with wide interior streets dedicated to meats and sausages, to fruit and vegetables, spices, tinned food, or fish, all under iron arches, stone, ceramics, and the large windows of the dome.

Chapter III, “Per la ciutat vella, 2”, in València per a veïns i visitants, by Joan Francesc Mira & Francesc Jarque. (Translated by the author.)

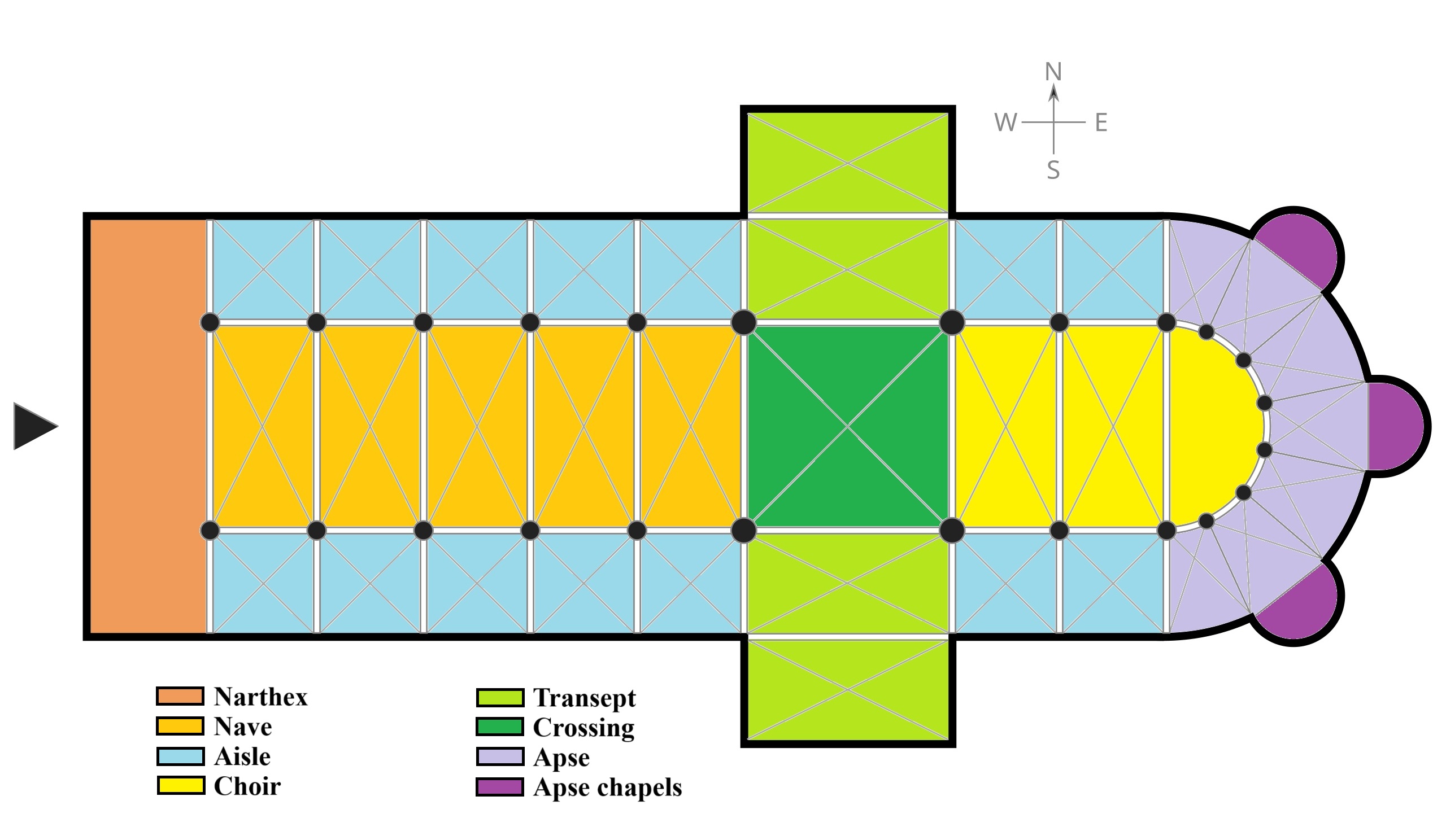

The use of this vocabulary extends even to technical descriptions, such as in the building’s file in the General Inventory of Valencian Cultural Heritage1. Here, the market is described as having ‘naves,’ a term used both in Valencian, Spanish, and English for the central hall of a church. It also details the naves’ layout as having “the shape of a Latin cross,” which is the traditional floorplan of pre-contemporary churches.

In this article we are going to dive a bit further into that. What does the design of a church look like? And does the Mercat Central de València indeed use that same design?

Vertical design: the basilica cross-section

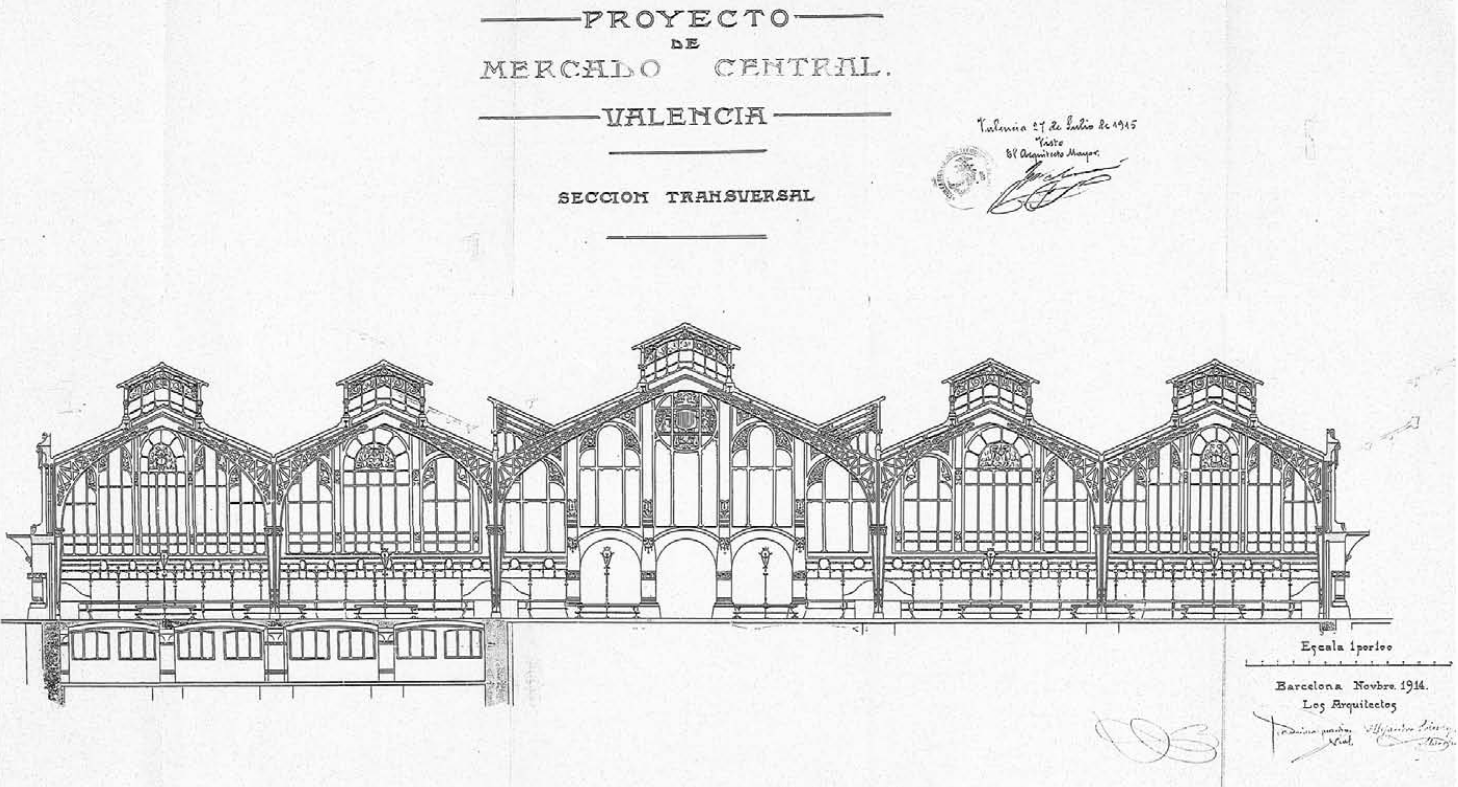

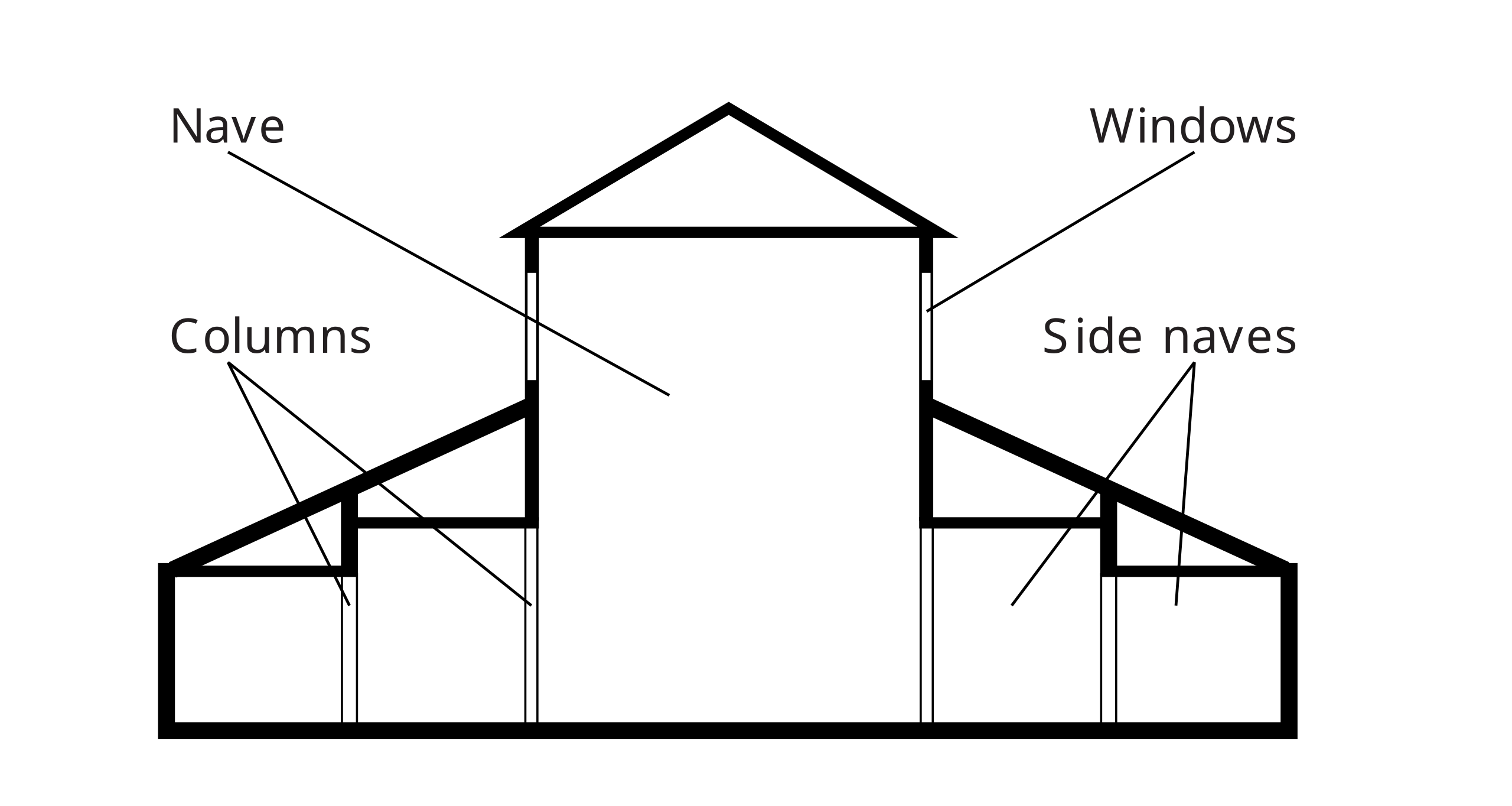

To understand what we are talking about, let us first look at a cross-section of the Mercat Central’s design. The image below is taken from the original design, and represents a cross-section from the southwestern part of the market. You can discern five naves, of which the central one is slightly higher. Each nave follows the same basic shape: a pitched roof, with an elevated section at the very top. In architecture, this shape is named ‘basilica.’

The secular basilica

The word ‘basilica’ probably makes you think of churches, but that is not its original meaning. In the Roman world, a basilica was a large public building, often constructed on the forum, the central town square. It would be a space for socialising, small-scale commerce, and most importantly, the courts of law.

These basilicae had a particular shape. A long rectangular hall ran the whole length of the building, with lower aisles on either side. The aisles were separated from the central hall by rows of columns. These columns supported an elevated section, the ‘clerestory’ in architectural terms, which often featured windows so that the nave received more natural light than otherwise possible. Finally, one or both ends of the main hall ended in a so-called ‘apse’, a semicircular area where the tribunal sat during court hearings. From the 4th century CE onwards, the early Christian church adopted this basilica-style for their new temples.

Nowadays, and already for a long time, the term ‘basilica’ is only used for a select few churches. While many churches use a basilica-style design, the word ‘basilica’ has now become an exclusive title. It is reserved for those temples with an exceptional status, for example due to their history or a special tradition of worship.

Why does the Mercat Central use a basilica-design?

The use of the basilica-design for markets was not revolutionary when the architects designed the Mercat Central de València. It had been in vogue for decades already, for example in Les Halles in Paris (1854-1857) and the Mercat del Born in Barcelona (1874-1876). Contemporary markets also used it, most notably the Mercat de Colón, which began construction around the same time as the Mercat Central – but finished much faster, in December 1916 already!

Why? The reason was simple. Fresh-food markets were massive buildings filled with perishable products. They needed illumination, so that clients could see clearly what they bought, and ventilation, so that bad smells would not linger and fresh air could circulate. The clerestory – the elevated part of the central nave – allowed for extra windows and blinds that made both illumination and ventilation much easier.

Of course, as architecture had developed significantly since Antiquity and the Middle Ages, architects adopted new materials to shape their basilica-style halls. Instead of stone, metal became the primary building material, making the construction much more lightweight than the typical church.

Horizontal design: the cathedral floorplan

When the Roman emperor Constantine formalised Christianity’s status in the Roman Empire, he ordered the construction of the first great churches in Rome, using the design of the earlier secular basilicas. His architects added one innovation: instead of a long, singular hall, they added a secondary hall, perpendicular to the central nave: the ‘transept.’

The new floorplan thus became a so-called Latin cross, the most well-known version of the cross in western Europe. The Latin cross’ lower arm extends longer than the other three, creating a t-shape (✞). Contrast that with the Greek cross, whose four arms are all the same length (✚). The Latin-cross floorplan grew popular during the Middle Ages, especially for larger churches such as cathedrals. Often, a tower or dome sat above the crossing.

Finally, many pre-contemporary churches feature spectacular stained-glass windows. These often showed biblical scenes and served an educational role, illustrating stories heard in the church. Moreover, when the light hit these windows, it not only illuminated the cathedral, but also introduced a celestial atmosphere in the building!

Crossing the Mercat Central

And curiously, not only does the Mercat Central de València feature a vertical basilica-shape, but it also uses a horizontal Latin-cross floorplan! From above, you can clearly recognise the Latin cross in the general market3. The four arms of the cross correspond to the four main entrances, one of which links up with the fish market. A dome rises over the crossing, a common element in Valencian churches.

Of course, the general market extends much beyond the basic cross (i.e. the nave, crossing and dome, and transept). On either side of that shape, secondary naves exist with a slightly lower height and, at times, irregular shapes. These additional naves obscure the cross-shape, but can still be explained within the context of a cathedral-floorplan. The first set of naves represent the aisles present in most churches on either side of the central nave. The second set represent chapels, which large churches often feature extending from the aisles and the apse.

Finally, like many churches, the perimeter wall of the market features stained glass windows. Rather than showing scenes of a biblical or other nature, the windows of the Mercat Central de València hold the city’s coat of arms (curiously, without the bat)! Architect and director of the Mercat Central’s renovation project Francisco Hidalgo Delgado indeed described these window panes as “cathedral-style.”

And the tower?

Every church has its tower, but looking at the Mercat Central, you might just miss them. That is right: “them,” because the Mercat Central has not just one, but two towers! Most medieval churches have their towers near the foot of the cross. The Cathedral of Valencia is no exception. That is just where we must look for them as well.

At the long end of the Latin cross we find a stone building adhered to the market. This is the administrative office of the Mercat Central’s Vendors’ Association. One of the main entrances leads through this structure. On either side of it, two small towers rise above the entrance, each crowned by a dome and a windvane. It might not be much, but towers they certainly are!

Coincidence or inspiration?

There is little to no chance of these design elements accidentally ending up in the Mercat Central de València. In the first place, its architectural style, Modernisme, has as one of its core tenets ‘holistic design,’ meaning that attention is paid to both the larger architectural plan as well as to the smallest details, such as decoration, materials, function, and so on. Nothing is by accident.

This is compounded by the fact that the architects were not just anyone. Alexandre Soler i March and Francesc Guàrdia i Vial were disciples of the famous Catalan architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner, who together with Antoni Gaudí lead the Modernisme movement. Soler i March would go on to direct the Architecture School of Barcelona4 and both him and Guàrdia i Vial would preside over the Association of Architects of Catalonia5. In short, they were recognised masters of their craft.

While Guàrdia i Vial did not have any notable experience with churches in his curriculum, Soler i March definitely did! He came from a deeply religious background, and constructed churches before and after designing the Mercat Central de València. Many of these shared design elements with the market: Latin crosses, naves, domes, and stained glass all made their appearance. Soler i March was extremely familiar with the inspiration for his market’s design.

Conclusion

The takeaway is that, indeed, the Mercat Central de València is a church. In a figurative sense it is a temple devoted to the meat, fish, and produce sold within it. This ‘Cathedral of the Senses’ celebrates the bounty of the earth and sea – a richness some might ascribe to God, and others to the industriousness of humanity, but that all can revel in!

But it also resembles a church in an architectural and practical sense. The centuries-old precepts for building churches, executed here with modern materials and techniques, provides the perfect shape and function for a well-illuminated, ventilated, massive public building. Valencian and Catalan Modernisme valued holistic design, in which function, shape, and meaning all came together to form one unified whole. The Mercat Central de València is thus a perfect example of this architectural style, well-deserving of its status as one of Valencia’s main monuments!

Sources

- De lo proyectado a lo construido. El Mercado Central de Valencia, by Francisco Hidalgo Delgado.

- El Mercado Central: 100 años de historia, by Gumersindo Fernández Serrano & Enrique Ibáñez López.

- El mercado modernista: el ejemplo valenciano. Estudio compositivo del Mercado Central y del Mercado Colón, by Laura Martín Anguita.

- Investigación integral de las unidades constructivas-arquitectónicas que definen el Mercado Central de Valencia como ejemplo singular de la arquitectura modernista valenciana, by Francisco Hidalgo Delgado.

- Mercado Central, Inventario General del Patrimonio Cultural Valenciano, Sección 1ª, Bienes de interés cultural, by the Generalitat Valenciana.

- Pequeño diccionario visual de términos arquitectónicos, by Lorenzo de la Plaza Escudero, Adoración Morales Gómez & José María Martínez Murillo.

- Revisión simplificada del Plan General de Valencia: Catálogo de bienes y espacios protegidos: Ordenación Estructural: Mercado Central, by the Ajuntament de València.

- València per a veïns i visitants, by Joan Francesc Mira & Francesc Jarque.

Footnotes

- Officially: Inventari General del Patrimoni Cultural Valencià. ↩︎

- You can see in this image that the basement only occupies one side of the building. Later changes made to the design, already during construction, expanded the basement to practically the whole market. ↩︎

- I am ignoring the fish market here because I want to keep this post short-ish, but that section in turn also resembles a church-element. Instead of the Latin cross, it follows the design of a Greek cross, typical for, for example, the Capillas de la Comunión which many Valencian churches had added externally in the 17th and 18th centuries. ↩︎

- Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona (ETSAB). ↩︎

- Associació d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, later Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya. ↩︎