Just south of Valencia’s city centre lies the neighbourhood of Ruzafa, one of the city’s most popular districts. Though its streets come across as relatively modern – most buildings go back a hundred years at most – its name hearkens back 1200 years! But what does the name Ruzafa mean?

Ruzafa means ‘garden’

It is almost obligatory for tour guides and websites describing the vibrant district of Ruzafa to mention that its name originates from Arab and means ‘garden’. The name comes from a palace and its garden built during the Caliphate period of Al-Andalus, the Muslim state in medieval Spain. Over time, the palace disappeared and a village sprung up that would eventually join the city of Valencia.

A good story! It illustrates the Muslim presence in a city where most physical remains of Al-Andalus have disappeared. It also draws attention to the use of Arab placenames in modern Spain. I have told it many times myself.

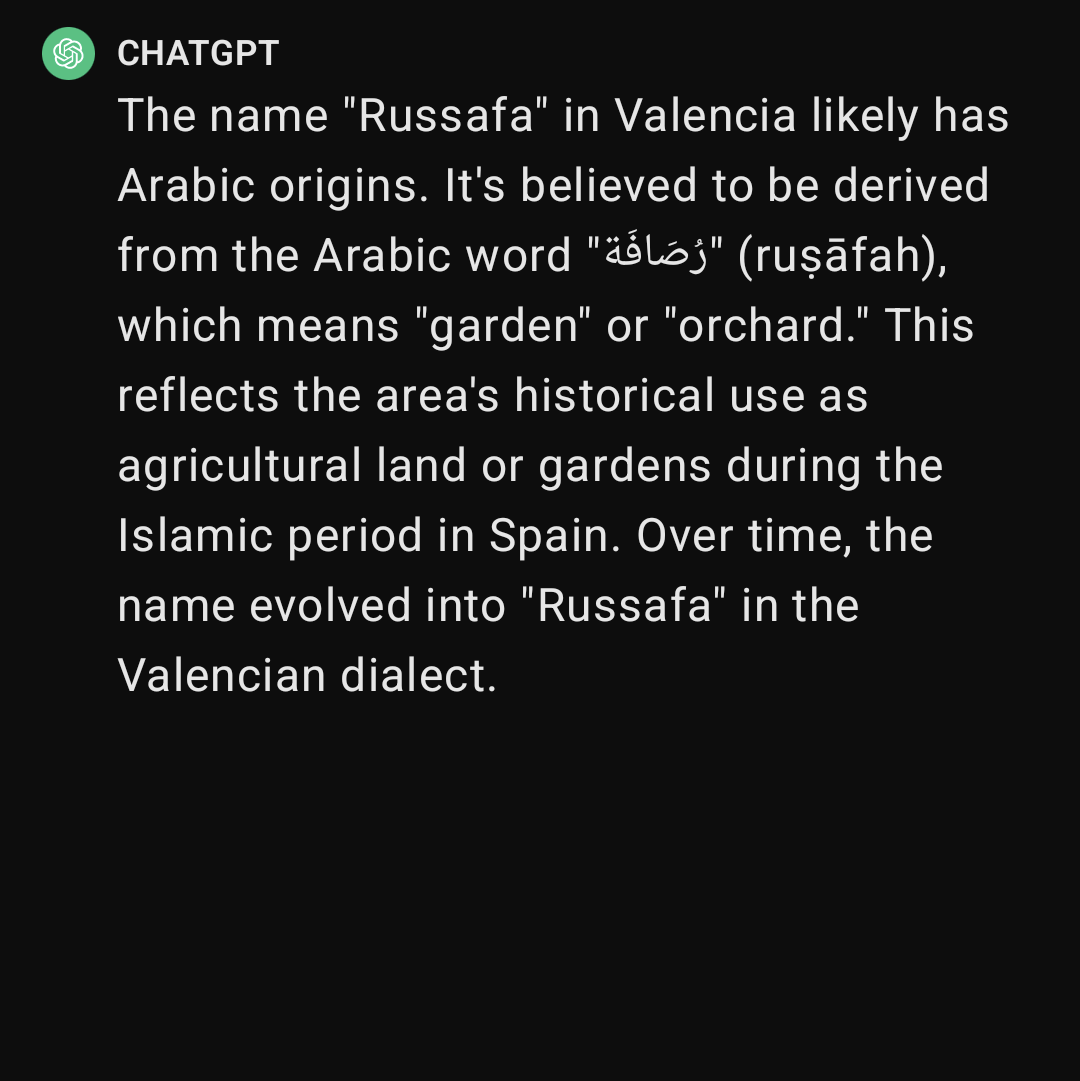

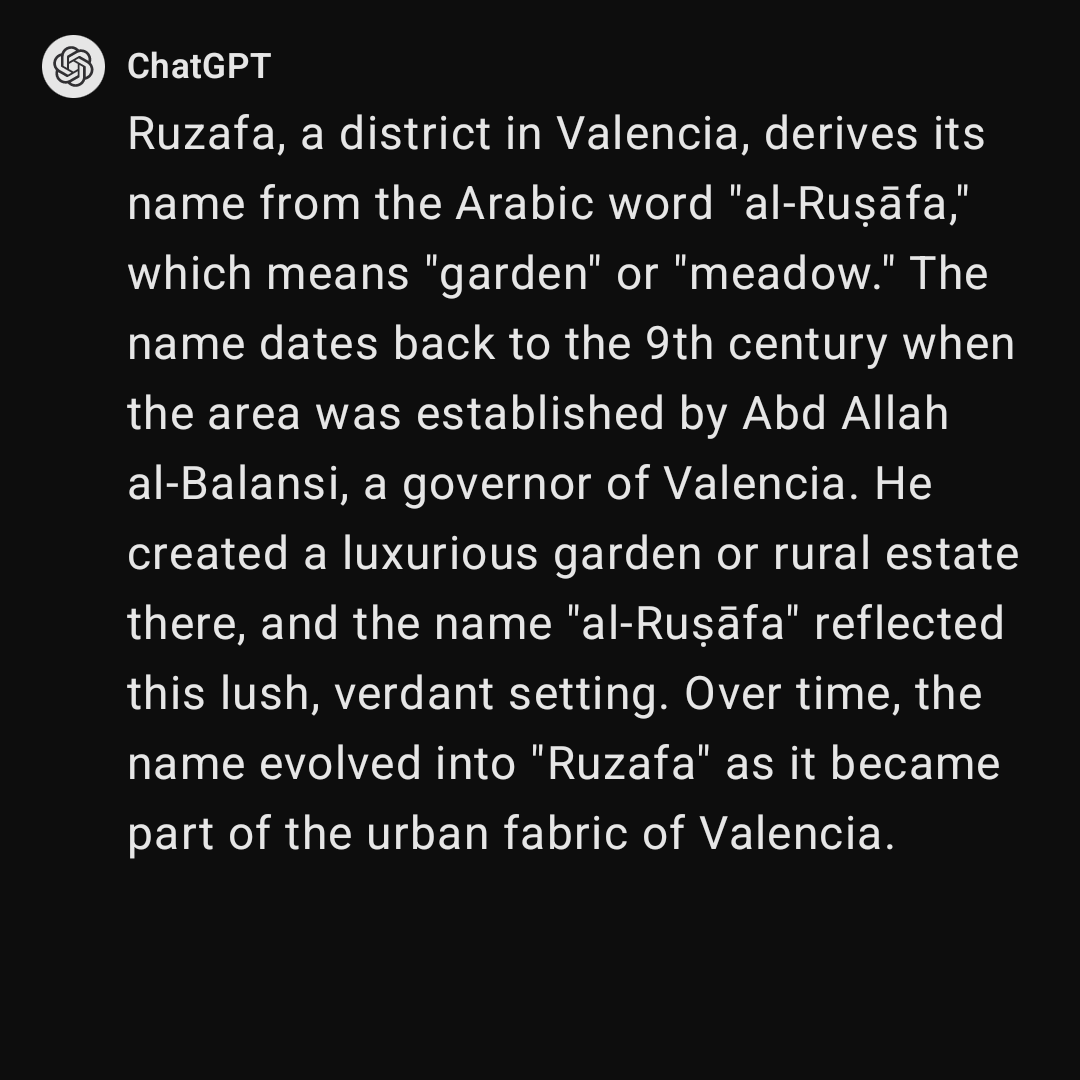

But is it actually true? I do not speak Arab, so I would not know if Ruzafa truly translates to ‘garden’, or to something else entirely. If it means anything at all…

Multiple definitions, languages, and Ruzafas!

Looking around on the internet, I found out a few basic facts. First of all, there is more than one Ruzafa! We have our Valencian neighbourhood, but Baghdad also features one: Al-Rusafa is one of the Iraqi capital’s old districts. Syria can boast two: Al-Rusafa in the western Masyaf district, and Resafa in central Syria. Returning to Spain, in Córdoba you can find an avenue and golf course named Arruzafa.2

Regarding the meaning of the word, a lot of ideas make the rounds. Most come down to the name Ruzafa originating in either Arab or Akkadian, an old Mesopotamian language. In the latter case, the original word would have been rasapa or rasappa. The most widespread definition is “garden” as mentioned above, but some also say it might mean “house of the governor”.

Simply said, it is complicated.

Ruzafa does not mean ‘garden’

What to do when multiple claims are being made about what a word means? Diving into a dictionary, of course! I found that the name Ruzafa equals to the Arab noun رصافة or رُصَّافَة. And the definition is… compactness, solidity, steadiness, or firmness.3 Quite a surprise, for someone expecting a greener meaning!

As I did not fully trust myself – again, I do not speak Arab – I decided to also double-check the claim of Ruzafa being a loanword from the ancient Akkadian language. Despite fading out of existence almost three millennia ago, we surprisingly enough have a dictionary of it!

I checked for entries looking like rasapa, rassapa, and other versions that seemed similar. Two words that to some extent resembled them came up: rasapu and rasadu. Colour me surprised when I saw that the first means to erect or to pile up [walls or buildings], and the second to be firm or to be solid! Both definitions are related to construction, and the latter almost perfectly matches with the Arab definition.

My guess would be that the Arab word indeed originated in Akkadian. However, its definition is very different from popular Valencian belief.

And yet Ruzafa was a garden!

Then why is our Valencian Ruzafa called that way? To answer that, we must tell the story of its builder, ‘Abd Allah al-Balansi.4 Al-Balansi – literally: “the Valencian” – was the governor of Valencia for over twenty years, starting in 802. At that time the Umayyad Caliphate ruled over Al-Andalus under the rulership of Al-Hakam, the nephew of Al-Balansi.

The munya

During his governorship, Al-Balansi constructed a country estate one kilometre south of Balansiya (the Arab name for our city). Such an estate, called a munya or almunia, was a typically Andalusian recreational residence with gardens, orchards, water fountains, and ponds. Rulers would build a munya a small distance away from their busy, stuffy cities to allow them to enjoy a bit of nature and tranquillity.

Around the munya its owner would often purchase some extra agricultural lands. The exploitation of these gave the elite a personal supply of food in periods of drought or other adversity. The people who worked these lands got permission to settle in the area in a so-called al-qaria.5 This happened in Ruzafa as well: around the area of the current Mercat de Russafa and the Iglesia de San Valero y San Vicente Mártir a small farming village provided food for its munya and the nearby city.

Ruzafa probably constituted the first Valencian munya. The Andalusian tradition of building these recreational palaces only really gained traction a generation later, under the reign of caliph ‘Abd al-Rahman II (822-852).

An example of a munya

A munya was not supposed to provide defensive value and thus did not feature thick walls, towers, and gate houses. Consequently, the passage of time often did away with them. After all, a castle or city wall often remained useful for later generations, while a pleasure garden needed a lot of maintenance for little objective return on investment. As such, the munya of Ruzafa disappeared without any trace. Fortunately, Spain does still posses a beautifully preserved munya in another city: the Generalife outside of Granada.

Built about five hundred years later, the Generalife stands a few hundred metres from the Alhambra palace-fortress, and less than a kilometre from the city itself. Though it has suffered many chances over the centuries, the basic elements can still be recognised. Outside there are pleasure gardens and agricultural fields, while inside beautiful patios and airy rooms provided its inhabitants with a paradise of tranquillity. The photos below can give you an impression of the Andalusian elite’s tastes!

Why Al-Balansi called his munya Ruzafa

The reason is nostalgia! Al-Balansi was the son of the first Umayyad emir, ‘Abd al-Rahman I.6 This man descended from the royal dynasty that had ruled in Damascus for almost a century. After a rebellion overthrew that government, ‘Abd al-Rahman fled to Al-Andalus and established an independent emirate there. Nonetheless, he always remembered his youth in Syria, and specifically the time he spent in the palace of his grandfather, caliph Hisham.

Caliph Hisham had built his palace far away from the capital Damascus, relatively close to the Euphrates River. The name of that spot? Resafa. This Resafa lay in the area that many centuries before had belonged to the Akkadian and Assyrian empires. It should then come as no surprise that its name originates in an ancient Akkadian word: to be solid.

When ‘Abd al-Rahman settled in his new fiefdom in Al-Andalus, he wanted a similar palace. And so, less than three kilometres outside of Córdoba, he acquired an estate and expanded it with “extensive gardens, and rare trees and fruits […] reproducing the architectural style, landscaping, and gardens of the Syrian Rusafa.”7 He gave it the Arabised name Ar-Rusafa, in memory of his grandfather’s home.

Finally, we return home!

His youngest son became governor of Valencia in 802. Like his father before him, he too cherished the memory of the beautiful munya where he grew up. Upon building a similar complex outside of his capital city, he nostalgically named it Ar-Rusafa, which over time would morph into our titular Ruzafa.

In a figurative sense then, Ruzafa does mean garden. After all, for the people of Al-Andalus the name referenced several of the great recreational palace gardens of their culture, whatever the literal meaning of the name. Just imagine: when you see a t-shirt with the print ‘Amsterdam’ you tend to think about the city, bicycles, or weed, not about the dam over the river Amstel. Likewise, an Andalusian reading the name Ruzafa was likely to reminisce about the munyas in Valencia, Córdoba, and Syria, not the sturdiness of their masonry!

There is no dwelling place like Ruzafa!

The Andalusian poet Ar-Russafi, who was born in the al-qaria of Ruzafa

The clouds give it spring showers.

Nostalgia for her and my family

Makes me suffer like the poet of Mosul.

A garden no more

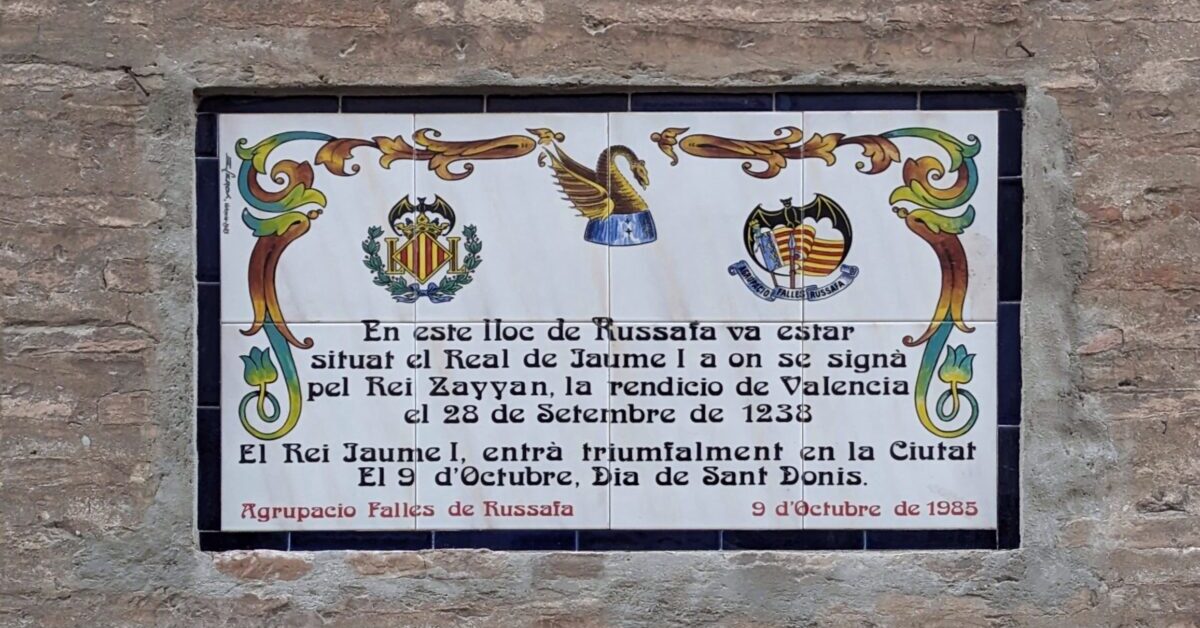

We do not know exactly when the munya of Ruzafa disappeared. Yet I wager we can put a specific ‘expiration date’ on the building, a specific year when the munya definitely no longer existed: 1238. That year the Muslim city of Balansiya came under siege by king Jaime I of Aragón. Jaime, in his autobiographical work El Llibre dels Fets, describes how Ruzafa was instrumental in the conquest of the nearby city.

The battle of Ruzafa

One day a small group of Jaime’s soldiers attacked Ruzafa on their own initiative. When Jaime was informed, he realised the group had put itself in a vulnerable position, so close to the city. Quickly mobilising his cavalry, the king rode to their aid. He barely prevented their demise, capturing the al-qarya of Ruzafa in the process.

When the “Saracens,” as Jaime calls them, did not counterattack, he moved the siege-camp to Ruzafa and installed his royal pavilion next to the village. His noble retinue occupied the houses of the al-qarya itself. The village was perfectly placed for the siege. It lay equidistant from two city gates, maximising response times to possible counterattacks from either one.

At no point in his quite detailed account of the siege and the happenings in Ruzafa does Jaime ever mention a garden, a palace, or anything of the sort. He only talks about the village’s houses, a square, a defensive tower, and the fields and irrigation canals. You would think that, if the munya had still existed, Jaime would have at least mentioned such a beautiful complex. He might even have taken up his residence there instead of in a tent!

El Llibre del Repartiment

With the conquest of Valencia achieved, Jaime turned to rewarding his knights and nobles for their support. He had a document redacted called El Llibre del Repartiment, which you could translate as The Book of Distribution or The Book of Donations. It listed hundreds of those who had rendered services to the crusade for Valencia, and the properties they would receive as compensation:

218. To Ladro, the house in Ruzafa in which he lodged [during the siege of Valencia], as it borders on three sides to the streets, and on the fourth to another adjoining house, and the garden in front of the aforesaid house, which faces the garden of P. Aznari, as it is enclosed with that house that is there. […]

353. To P. Remiriç and Michaeli his brother, ten parcels8 in Ruzafa and the house in Ruzafa where he was hosted by Bg. d’Entença [during the siege of Valencia], and the house of Mahomad Abinçalema in Valencia, with that tent which is in front of the aforesaid house, for the work of the stable. June 3rd.

627. To Ermengaudus of Minorisa, the house of Mahomet Abincorçel, the father of Jucef, and six parcels and one vegetable garden in Ruzafa. September 17th.

El Llibre del Repartiment del Regne de València

The size of Ruzafa

In total the book recorded 664 donations, of which 55 entries mentioned Ruzafa. I tallied them up, and have found that Jaime doled out 49 (farm)houses, and just over two hundred parcels of farmland. That means that at the time of Valencia’s conquest, Ruzafa constituted a significant village – and of course a good number of independent farmhouses spread out over the countryside.

Interestingly, the parcels added up to over six hundred hectares. The current neighbourhood Ruzafa does not even measure seventy hectares. We should not forget, however, that Ruzafa used to occupy much more space before its incorporation into the municipality of Valencia. Its rural territory stretched out all the way to La Punta, close to El Pinedo!

Conclusion

So yes, the neighbourhood Ruzafa in Valencia got its name because it was a palace garden! But also no, the name does not literally mean ‘garden’, but rather ‘solidity’ or more generally something that is well-constructed. The name arrived in our city through a series of nostalgic references, geographically going all the way back to Syria, and etymologically going back all the way to the Assyrian Empire, some three thousand years ago!

It is a shame that nothing survives of Valencia’s first recreational palace garden, as it must have been a gorgeous place to visit. Imagine if in the centre of Ruzafa a green oasis still remained in the style of Al-Andalus, or maybe similar to the Jardins de Montfort… Nonetheless, we are now left with only the name, along with a lively neighbourhood to enjoy a drink and some tapas!

Sources

- Anàlisi toponímica de l’Horta de València. Integració dels enfocaments clàssic i crític per a la reconstitució i revaloració del seu paisatge, by Joan Carles Membrado Tena & Emilio Iranzo García.

- El Llibre del Repartiment del Regne de València, by King Jaime I of Aragón.

- El Llibre dels Fets, by King Jaime I of Aragón.

- Entre Tierra y Fe: los musulmanes en el reino cristiano de Valencia (1238 – 1609), by the Universitat de València.

- Granada y la Alhambra: arte, arquitectura, historia, by Rafael Hierro Calleja.

- La Valencia Musulmana, by Vicente Coscollá Sanz.

- Supervivencia de paisajes rurales en urbes a través de la toponimia. El caso de Valencia, by Joan Carles Membrado Tena & Ghaleb Fansa Saleh.

- The Assyrian dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- The garden in Umayyad society in al-Andalus, by Miquel Forcada.

Footnotes

- These screenshots have been taken in the same app, about one month apart. Remember that ChatGPT is not truly intelligent, even though it is called AI. It ‘only’ predicts what words is statistically likely to follow the preceding one, based on a massive input of texts in its training phases. That means that these answers are not actually thought about, but rather represent what the websites and texts of ChatGPT’s input have often repeated about Ruzafa. ↩︎

- In some of these you see the various spellings of Ruzafa preceded by an al or ar. This is the Arab article ‘the’. ↩︎

- Found on Wiktionary. ↩︎

- Arab names are looong. This man’s full name is ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Abd ar-Rahman ibn Mu´awiya al-Balansi. ↩︎

- The word al-qaria lies at the root of the Spanish word alqueria (farmstead or hamlet in English). It was bigger than just a single farm and more like a hamlet or small village with extensive fields around it. All these fields and the village itself were the property of one person or family. Its agricultural production was often focused on providing food to a nearby city. You can compare it in size and function to the Roman villa. ↩︎

- Full name: ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Mu’awiya ibn Hisham. Compare this with Al-Balansi’s full name, and you might start to see a pattern! ↩︎

- The garden in Umayyad society in al-Andalus, p. 353, by Miquel Forcada. ↩︎

- I have translated as ‘parcel’ a term often used in El Llibre del Repartiment, which is jovata or jovada. This is an archaic agricultural term for a plot of land that can be tilled by a single ox in one day. In medieval Valencia one jovada equalled 2,99 hectares. ↩︎