About thirty kilometres to the south of Valencia lies an ancient battlefield. Not even 48 hours after Valentia Edetanorum was reduced to ashes in 75 BCE, this area witnessed one of the great battles of the Sertorian War: the battle of Sucro.

Last time, we left the Sertorian War in medias res. Pompey defeated the army which defended Sertorius’ northern flank at the Turia river. He took Valentia, and we saw how his army punished its defenders and burned the town to the ground. Meanwhile, general Perpenna escaped the disaster and fled southwards in an attempt to join the remnants of his forces with Sertorius himself. What happened next?

A question of timing

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the battle of Sucro, let us shortly discuss when this might have happened. Some ancient writers say that the battle of Sucro happened the same day as the battle of the Turia, but to me that seems far-fetched. The town Sucro lay some thirty kilometres south of Valentia, right next to the river of the same name.1 Historians estimate the regular marching speed for a Roman army at almost twenty kilometres a day.2 A general might in an extreme case be able to push that to thirty – but to do that in addition to fighting in the morning at the Turia and in the evening at Sucro? I would call that improbable at best.

The timeline, in my opinion, thus looks as follows:

Day 1: Pompey crosses the Turia, and defeats the army of Perpenna outside the walls of Valentia Edetanorum. He then takes the city, punishes the rebels there, and sets fire to the buildings. Possibly that same day he starts to march south already, covering some of the distance to Sucro (not the whole thirty kilometres; his soldiers must have been exhausted).

Day 2: Pompey covers the remaining distance to Sucro, and in the afternoon or early evening finds Sertorius’ army there, reinforced by the remnants of Perpenna’s forces which Pompey defeated yesterday.

The battle of Sucro

In the end Sertorius and Pompey faced off. Both were in a rush to get things over with. For Pompey the hurry was rooted in pride: he was keen on defeating Sertorius all by himself. His ally (and superior) Metellus was within a day’s march of the battlefield, and if he arrived in time to assist in the battle, Pompey would have to share the podium. Sertorius must have been nervously watching the horizon for Metellus’ arrival as well. Fighting both Metellus and Pompey simultaneously would have meant certain defeat for his outnumbered forces.

A late start

The two armies drew up their battlelines. Plutarch writes that Sertorius took the initiative and attacked first, while it started to get dark. If this battle truly took place the day after the battle at Valentia, you might wonder why it took them until evening to start the fight. Partly this would have been due to Pompey’s march south from Valentia, but another factor could have played into it: a long wait. Often armies formed up for battle for hours without actually engaging. Generals might want to wait for the enemy to make a mistake, or have chosen such a good defensive position that they were not willing to abandon it.

The trigger for Sertorius’ attack was darkness itself. He considered that his men, part of whom were locals, knew the terrain much better than Pompey’s soldiers did. Under the cover of darkness his army would have the advantage, “either in flight or in pursuit,” depending on how the battle would go.

Attacks…

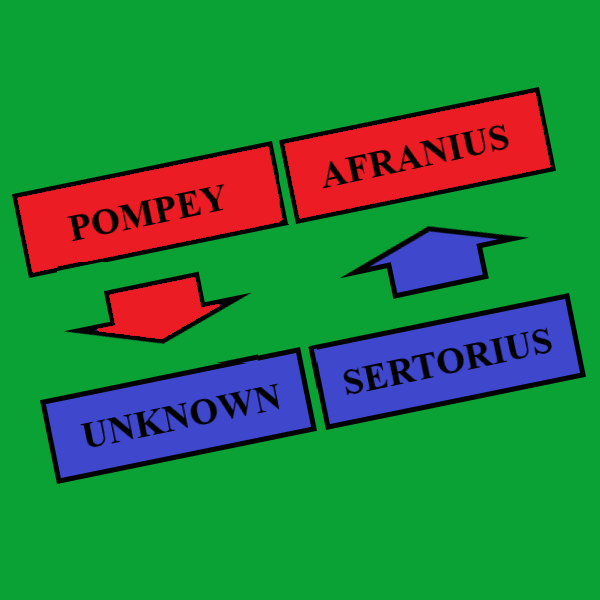

Armies were often too large to led into battle by one man alone, so usually a commander commanded one element of his forces himself and delegated command of the rest. At Sucro, Sertorius positioned himself on the right wing of his army and gave the left wing to another officer. Pompey did the same, delegating his left wing to Afranius (yes, that Afranius). This placed Pompey and Sertorius on opposite sides of the battlefield, with the latter facing Afranius instead.

When the battle started, Sertorius and Pompey each showed their military talents: both managed to push their opponents back. Of course, this meant that both armies’ right wings advanced, while their left wings gave way, and so the armies slowly started circling each other counter-clockwise.

…and counterattacks

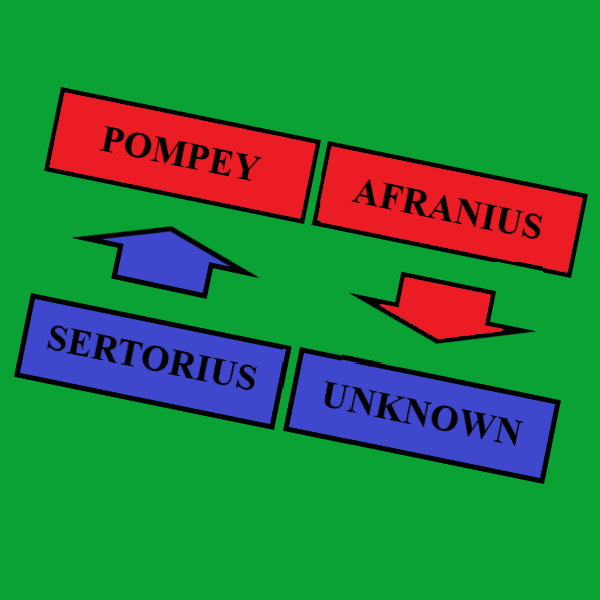

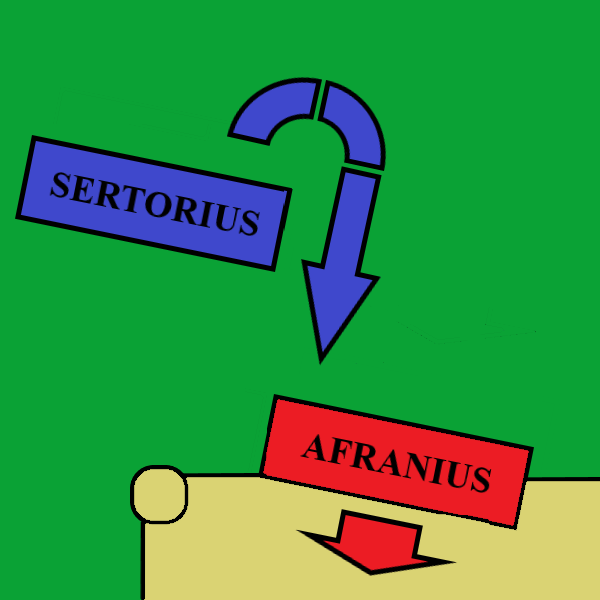

Sertorius, noticing this, decided he had to act. He turned over command of the right wing to one of his generals, and moved to the left. On the way he encountered soldiers who were fleeing from Pompey’s attack. A fragment remaining from ancient historian Sallust’s writings has Sertorius reprimand his men: “No one [will] recognise as true men those who left the battle unarmed.” They rallied around him and turned back to fight, reinforcing the wavering lines. Pompey’s advance was stopped, and a very successful counterattack began.

Pompey’s brush with death

In the heat of battle, Pompey came close to being killed. Plutarch describes how “Pompey, who was on horseback, was attacked by a tall man who fought on foot.” The attacker wounded Pompey with “a dangerous wound from a spear in the thigh.” Pompey managed to cut off the hand of his assailant, but to escape the rapid advance of Sertorius’ men he had to jump off his horse and leave it behind. That proved to be his salvation, as his horse wore a richly decorated harness. A significant number of soldiers tried to capture the horse as spoils of war instead of chasing after Pompey, arguing with each other about who would get what.

Expand: Did ten thousand soldiers really die here?

A Roman writer, Orosius, would later claim that 10.000 of Pompey’s soldiers were killed here. If that number seems familiar to you, that is because at the battle just before this one, at Valentia, the death-toll supposedly also numbered 10.000. Coincidence? As noted in a footnote to the last post, this might be rooted in the translation of the Greek word for ‘myriad’. This word can either mean the literal number 10.000, or be a figure of speech meaning ‘a lot’. Additionally, Orosius wrote this almost 500 years after the fact, and so his numbers should be taken with a pinch of salt. He might even have confused the number given for the battle of the Turia with those of the battle of Sucro. They both happened within a 48-hour timeframe, after all.

Afranius suffering from success

While Pompey ran for his life, his second-in-command Afranius had an easier time of it. After Sertorius had left that side of the battlefield, Afranius faced an inferior general and started to gain ground. Either due to the darkness or the confusion of battle he did not see that Pompey retreated and so did not stop to help him. He pushed right through Sertorius’ right wing and soon reached the latter’s camp. His soldiers entered the tents and started plundering, completely out of Afranius’ control.

With Pompey abandoning the battlefield Sertorius returned to his camp, only to find Afranius’ forces there, disorganised and fully occupied by the looting. The Sertorian army attacked them in the rear and managed to kill a great number of these soldiers before Afranius could retreat.

And so, the first engagement of the battle of Sucro ended. Overall, the battle had been a chaotic fight with several attacks and counterattacks, and no clear victory for either side. Once again, the stories about Sertorius proved to be true: when he was in charge, he would almost always win. But he could not be everywhere at once to cover for his officers’ shortcomings…

Another day, another chance?

As the sun rose over Sucro the next day, Pompey and Sertorius took their armies to the battlefield again. Once more the men deployed, and everyone waited for the sign to attack. But then Metellus arrived.

Metellus was the highest-ranking general Rome had sent to Hispania to defeat Sertorius. Pompey must have been rather disappointed with the arrival of his ally and commander-in-chief. After all, just yesterday he had thrown himself and his army into battle with the explicit objective of crushing Sertorius before Metellus could arrive to share the glory. Yet here he was, probably arriving from the direction of Saetabis, nowadays Xàtiva.

Sertorius had even less cause to celebrate: he had no possibility of victory over the combined forces of Pompey and Metellus. His supposedly strong defensive position between Valentia and Sucro had failed to keep his enemies apart. Nonetheless, though he had no way of winning, there was no reason to lose either. Sertorius executed a well-practiced, almost guerilla-like manoeuvre: a chaotic, scattered retreat.

His men were accustomed to scatter in this way, and then to come together again, so that often Sertorius wandered about alone, and often took the field again with an army of a hundred and fifty thousand men, like a winter torrent suddenly swollen.

Plutarch, Life of Pompey 19.4.

Pompey and Metellus remained behind, facing each other instead of their enemy. Considering the fierce jealousy that Pompey felt vis-à-vis his commander, their encounter was surprisingly polite and courteous. Plutarch tells us that Pompey showed Metellus all due signs of respect (probably while grinding his teeth). Yet Metellus would have none of it and treated Pompey as an equal, regardless of his own superior age, rank, and experience.

Aftermath of the battle of Sucro

Sertorius army thus escaped from the battle of Sucro and retreated inland. His men fought a true guerilla campaign in Valencian lands, attacking the supply lines Metellus and Pompey had set up. Soon the Romans had to retreat from Valentia as provisions became almost impossible to obtain. Valentia and its surroundings remained behind, utterly ruined by the Sertorian War.

In the end, Sertorius would not be victorious. A few years after the battles of Valentia and Sucro his own men betrayed him, just like Viriatus. In fact, Perpenna – the man who failed to defend Valentia against Pompey – led the conspiracy. He took over command of Sertorius’ forces, but unfortunately for him, no one ever accused Perpenna of being a good general. Soon Pompey captured him and had him executed for treason.

Conclusion

And so the Sertorian War came to an end. It would be the final surge of indigenous identity and culture in Hispania. Afterwards Iberian tribes such as the Edetani around Valencia gradually lost their significance. They were integrated in a new society which was truly Roman. For Valentia as a city it also signified a violent end – for now.

For one person this period was the beginning: Pompey. His new-won glory and fame helped him rise every higher through the ranks of Roman society and soon earned him the monicker “the Great.” Decades later he would make a political alliance with the most famous Roman of all time: Julius Caesar. When Caesar grew too powerful, Pompey attempted to stop him. The civil war that ensued destroyed the Roman Republic and cemented Caesar’s power as he became dictator for life. Pompey the Great would not live to see it.

Sources

- El trazado de la Vía Augusta desde Tarracone a Carthagine Spartaria. Una aproximación a su estudio, by José G. Morote Barbera.

- Historia de la Hispania romana, by Pedro Barceló & Juan José Ferrer Maestro (2022, first edition 2007).

- Historiae II, 48-52, by Sallust.

- Histories against the Pagans, book 5.23, by Orosius.

- L’Albufera de València. Comercio y frecuentación ultramarina entre los siglos VI y II a.C. by José Pérez Ballester (in “SAGVNTVM: Papeles del laboratorio de arqueología de Valencia, Extra-17. El sucronensis sinus en época ibérica,” edited by Carmen Aranegui Gascó).

- La destrucción de Valentia por Pompeyo (75 a.C.), by Llorenç Alapont Martín, Matías Calvo Gálvez & Albert Ribera i Lacomba.

- Life of Pompey, 19, by Plutarch.

- Life of Sertorius, 19, by Plutarch.

- The Civil Wars, book 1.110, by Appian of Alexandria.

Footnotes

- The town Sucro’s current name is Albalat de la Ribera, and the river Sucro equates to the Xúquer or Júcar river. ↩︎

- See this discussion of military logistics in the ancient world of the ACOUP blog. ↩︎