After its foundation in 138 BCE the town of Valentia Edetanorum quickly attained an important role in the area. Unfortunately for the first Valencians this importance put the town right in the bull’s-eye of the Roman war machine… Just 63 years after consul Brutus founded Valencia, general Pompey the Great brutally razed it to the ground. But why did the Romans destroy a city they founded themselves?

As often happens, the further you go back in time, the scarcer information becomes. Reading up on the history of Valencia, this is no different. Its Roman era suffers from very summary descriptions. An event which took place in 75 BCE is often described with just a single sentence. The archaeological centre L’Almoina, for example, writes: “Valentia was destroyed by General Pompey in 75 B.C. and afterwards the city was left deserted.”

Just over a dozen words, and yet hidden behind them we find an extremely traumatic time for the earliest inhabitants of Valentia Edetanorum. Let us see what more there is to this story and shine some light on our favourite city’s early death and rebirth!

A prologue: Romans fighting Romans

About sixty years after the Romans had founded Valentia, their world was in turmoil. The Romans had fought for almost a decade with their own allies and amongst themselves. Sulla, the leader of a conservative faction, had won the last civil war and become dictator. His opponents, reformists who wanted to open Roman citizenship to Rome’s allies in Italy, were violently purged or exiled.

In these civil wars two men had risen to positions of power, but on opposing sides. On the one hand, a man called Pompey managed to make a name for himself by raising a personal army and supporting the conservative Sulla. Beyond political and material support, he had also shown himself to be an effective general in battle.

Sertorius

Meanwhile, Sulla’s enemies included the experienced politician and general Sertorius. During the last civil war Sertorius had been gathering support for the reformist cause in Hispania. When Sulla achieved victory and became dictator, Sertorius escaped the purge due to his presence in Hispania. Nonetheless, Sulla deposed him from his position as governor and he was forced to flee to Africa, where he immediately started planning a vengeful return. After all, he did not accept Sulla’s legitimacy as ruler of Rome, and consequently, Sulla’s authority to depose Sertorius as governor of Hispania. Sulla’s Civil War might have been officially over, but in 80 BCE Sertorius returned to Hispania with an army, and so kickstarted the Sertorian War.

War in Hispania

Sertorius’ invasion of Hispania went rather well. Although the Roman government quickly sent general Metellus to defeat him, Sertorius continually slipped away. He moved fast and avoided a direct confrontation, while convincing more and more local tribes to join his cause. His army now included Romans, Italians, Libyans, Lusitanians (remember them?), Celtiberians, and other Hispanic tribes. After three years of fighting Sertorius controlled a large part of the Iberian Peninsula, including the mediterranean coast from the Ebro valley all the way down to Denia. Valentia Edetanorum also joined the Sertorian side.

Why did Valentia join Sertorius?

We are never told why exactly Valentia chose to fight with Sertorius. If we speculate, we can think of some possible motivations. Possibly the leadership of Valentia knew Sertorius personally. He had spent years working for the Roman government in Hispania and might have made connections in Valentia, which was one of the few officially Roman settlements in Hispania at the time. Another reason might simply have been that Valentia negotiated a beneficial deal with Sertorius to join the war on his side in exchange for something.

But there might have been a personal reason for this decision as well. After all, Valentia’s first settlers were – probably – people from Campania in Italia. During Sulla’s Civil War, Neapolis, one of the largest cities in Campania was conquered by Sulla’s army. As punishment for its choice to fight against him, Sulla had the city destroyed and the population massacred. If the Valencians kept in touch with their relatives in Campania (not too surprising for a colony depending on its homeland, and within two generations of its foundation), they might have lost relatives in this massacre. Such an event could have motivated them to join the enemies of Sulla to pursue revenge.

Pompey thwarted near Valentia

General Metellus could not put an end to Sertorius’ resistance, as every time he got close to one of his armies, it moved away faster than he could get there. The Roman senate decided to send another army to Hispania, commanded by general Pompey. He crossed the Pyrenees into nowadays Catalonia in 76 BCE and marched south into the region of Valentia: Edeta. His motivation was possibly to secure the road from Tarragona to Cartagena.

Close to the city of Valentia lay the town of Lauro (nowadays Llíria), where Pompey’s army came face-to-face with Sertorius. Sertorius soundly defeated Pompey, who had to turn back. If Sertorius wanted to pursue him, he never got the opportunity. Far to the south, near nowadays Sevilla, one of his generals made the mistake of directly confronting Metellus and lost heavily. Sertorius was forced to let Pompey go free so he could address the situation in the south.

The Battle of Valentia

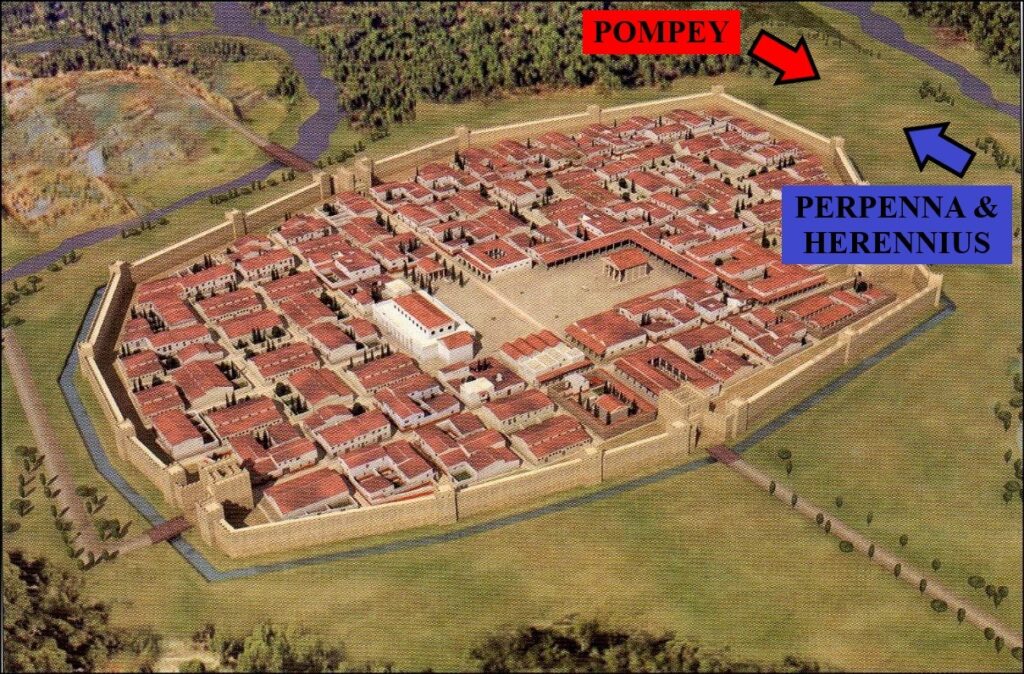

75 BCE would be the decisive year of the Sertorian War. Metellus from the south and Pompey from the north could now seriously threaten Sertorius, and if these two generals could join forces, it would be the end of Sertorius. To prevent this, he took control of an easily defendable area: the plain running from Valentia Edetanorum south to Sucro.

The theatre of battle

This was a tactically sound move. Across this plain, from north to south, ran the Via Heraklea (in later times, the Via Augusta). The Roman army depended on large roads to move fast. The points where main roads crossed rivers were vital to control; large groups of people carrying heavy gear and travelling with pack animals could hardly swim across rivers. If you could lock down those places were bridges crossed the water, or where the rivers were shallow enough to ford them on foot, you could stop an enemy in their tracks.

This was exactly Sertorius’ plan. Pompey and his legions were to the north of the river Turia, while Metellus’ army was to the south of the Xúquer. Right in the middle of them was Sertorius. The rivers created natural barriers for his enemies, who could only reasonably cross at two points: Valentia and Sucro, both controlled by Sertorius’ armies. As long as Pompey and Metellus could not somehow join their two armies together, Sertorius was confident he could win any battle against either general.

Pompey attacks

When you read the Roman historians’ commentaries on the Sertorian War, they often repeat that Sertorius was an amazing general who rarely suffered defeat. Even if a battle went sideways, he would still somehow manage to save his army and get out. However, his subordinate commanders apparently did not live up to his genius. Unfortunately for Valentia, Sertorius appointed two generals to guard his northern flank at Valentia Edetanorum: Perpenna and Herennius. He himself took up the southern front at Sucro.

And sure enough, Perpenna and Herennius failed in their main task: keeping Pompey north of the river. We do not know how, but Pompey managed to move his army across the Turia without his enemies being able to stop him. He forced his opponents into a bad position, according to ancient historian Sallust: “between the wall [of Valentia] on the left and the river Turia on the right, which flows past Valentia at a short distance.” This seems to indicate that Pompey attacked Perpenna from the west, in the direction of the sea.

The battle goes badly for Perpenna and Herennius. They rapidly lose ten thousand soldiers1, Herennius is captured, but Perpenna manages to escape with a part of the army and flees the battlefield. Presumably he takes the Via Heraklea and marches as fast as he can towards Sertorius’ camp at Sucro, about thirty kilometres southwards. The next day a great battle would be thought there.

The sack of Valentia Edetanorum

With Perpenna and Herennius defeated, Valentia is left to the mercy of Pompey. And he is in a vengeful mood. We do not have a lot of literary evidence of what exactly happened to Valencia after the battle of the Turia. What we do have, in this case, is a letter that Pompey wrote to the Roman senate sometime after the battle, where he almost tells us about the sack of Valentia, but then decides not to:

Why need I enumerate our battles or our winter campaigns, the towns which we destroyed or captured? Actions speak louder than words. The […] battle at the river Turia, and the destruction of Gaius Herennius, leader of the enemy, together with his army and the city of Valentia, are well enough known to you.

Sallust, 2.82.

So, until 1987, we did not know a whole lot, and some even doubted that Valentia was destroyed at all. But in the 1980s excavations started at the L’Almoina Archaeological Centre in Valencia, and the ground gave up its secrets. At first, researchers found all throughout the archaeological dig a thick layer of rubble and traces of fire damage, roughly separating the layers of the Republican and Imperial era of Roman Valencia. And then, in 1987, fourteen skeletal remains were found.

Pompey’s victims

Fourteen bodies, all of them male, and most of them aged between 17 and 25 years old. One was older, estimated at around 35 years of age. All the skeletons indicated that they were muscular men, and had been used to heavy labour. Their dental health was consistent with the Roman military diet. In short, they were soldiers. But what struck the archaeologists above all, was the brutal violence to which each and every body was submitted: they found “a scene as cruel as it was spectacular. The archaeology placed in front of our very eyes was the direct testimony of the brutality and horror of the Roman social war in the city of Valentia.”

The archaeologists painstakingly researched the human remains they found.2 Every man had been tortured heavily. Hands, arms, and legs had been cut off by rough sword strikes. Several soldiers were decapitated. One man, the oldest of them, was empaled by a spear. And the worst of it all, was the archaeologists’ conclusion that all this happened to them while they were alive and restrained. The repetition in the type of amputations showed that the torture was systematic and premeditated. In short: this was Pompey’s punishment for their rebellion. The archaeologists speculated:

The soldiers of Sertorius, once defeated and captured, were mutilated, and sacrificed in an act of punishment and public chastisement, coercive and exemplary. Most probably, a group selected from the defeated prisoners, maybe due to their rank, were taken to public, central spaces of the city to show them to its rebellious inhabitants and to be cruelly tortured and executed to frighten the living by using the dead, after which, as a final punishment, the city was reduced to ashes.

Alapont Martín, Calvo Gálvez & Ribera i Lacomba, p. 27.

Apart from these human remains, the researchers found weaponry, including Roman javelins (the famous pilum), billhooks, elements of shields, a knife, and a part of a helmet. In the public bathhouse, which was also destroyed during the sack, they found a stone ball: a piece of ammunition from a ballista. In one part of the excavations a hidden cash deposit was found. The most recently minted coin in this treasure was made in 77 BCE, two years before Valentia went up in flames.

And up in flames the city went! The evidence of that is omnipresent in L’Almoina and other archaeological digs around the city. Due to the absence of non-military bodies, I would guess that the civilian population of Valentia was largely imprisoned and deported. They might even have been sold into slavery, a common practice at the time. After the battle of the Turia and the sack of Valentia, sixty-three years of Valencian history came to an end, at least for a while.

Rebirth: what happened after the destruction of Valencia?

It took a long while for Valencia to return to the spotlight. For decades the town remained unmentioned in any historical literature. When exactly the city was repopulated, is unclear. The main archaeological centre of Valencia, L’Almoina, states that this happened “at an undetermined moment between 5 B.C. and 5 A.D.” under emperor Augustus, while others think it might have happened already ten years earlier.

The timeline challenged

There are, however, some dissident voices. It might be that Pompey did not completely erase Valentia, and that the city was never fully deserted for sixty or seventy years. The evidence is thin, but it exists; an inscription discovered in 1844 in Cossignano, a town in Italy, close to the Adriatic coast:

Lucius Afranius Auli, son of the consul and colonist of the Valentinian colony.

A short sentence, but it breaks the widely accepted timeline of Valentia’s destruction and rebirth. The inscription is from the year 60 BCE, fifteen years after Pompey burned Valentia. And Lucius Afranius is not a random Roman; he was Pompey’s second-in-command during the battles around Valentia!

In 60 BCE Afranius had climbed up the political ladder and was now consul of Rome, the highest political office one could attain at the time. In that same year he ordered the inscription above to be placed in his town of birth, Cossignano. An inscription explicitly connecting him to a town which he supposedly helped destroy fifteen years ago, and should have been in ruins at that time!

How is this possible? You could suggest that the inscription referred to one of the other Valentias existing in Roman times, for example in nowadays France, Italy, or Morocco. But no known connection exists between Afranius and those Valentias, while his presence in our Valentia is specifically described by our sources. The conclusion could then be that some members of Pompey’s army, such as Afranius, were rewarded with properties in the conquered area, and that Valentia remained partially populated.

Stagnation then!

Assuming Afranius’ inscription indeed talks about our Valentia, some human activity must have remained or quickly resurfaced after Pompey destroyed the city. This presence must have been significant enough to be named; you can hardly imagine a Roman consul bragging about belonging to a community of a handful of people!

In any case, you probably should not imagine a huge, thriving city either. I wager that the city itself would be largely ruins, with some buildings repaired and repurposed for a relatively small group of people. The excavations of L’Almoina have shown signs of having old ruins being repurposed in this way. The locals at this time would most likely have been working on the farmlands around the city, making a living for themselves, but not really growing the local economy.

A feast!

At some point, however, the Romans became interested in Valentia again. We do not know exactly when (estimates range from 15 BCE to 5 CE), and we do not know exactly why, though we can speculate that it was for similar reasons as the city’s initial construction. The location on the Via Heraklea, near the coast, and next to the Turia river was a strategic place to control.

Whenever it was, the Roman return to Valentia was reason to celebrate! When the Romans established – or in this case, re-established – a city, they would throw a feast, eating and drinking in honour of the gods. At the end, they would throw all the remains of the feast, such as food, utensils, cups, and plates, down into a well and cover it up. After all, you could not in good consciousness reuse a plate used in a holy ritual banquet! In this case, everything was thrown into the old well of the only building which had survived Pompey’s rampage: the temple of the god Asclepius. This well was found in L’Almoina, where you can still go see it today!

Real growth would take a while to come about. Between the destruction of Valencia by Pompey and its real come-back in the 50s CE, the Roman Republic would have fallen, and three Roman emperors would have come and gone. When Claudius ascended to the throne, followed by Nero and then the Flavian dynasty, Valentia Edetanorum would finally be back as a major urban centre, with a new forum, large public buildings, and even a large circus for racing events!

Conclusion

That concludes the story of Valencia’s early death and rebirth: a story which reflected the times of Romans and their allies fighting amongst each other, and – as in every war – civilians stuck in the middle. It also reflected the times in its brutality. Destroying urban centres for their part in a rebellion happened often. Just a few years before Valentia was destroyed, Sulla’s armies sacked and burned Neapolis. For Valentia this might have been a warning, but it also might have been a driving force for joining Sertorius. Neapolis was a Campanian city, and the Roman Valencians might have had familial roots there. Ultimately, if Valentia attempted to avenge its inhabitants’ relatives, it failed utterly and faced Pompey’s retaliation for it.

When the flames died down, the city virtually disappeared for sixty to eighty years. All in all, 125 years of stagnation and (political) irrelevance would go by before the city returned to greatness. And from that new Valentia, our modern Valencia would one day come about!

Sources

- El trazado de la Vía Augusta desde Tarracone a Carthagine Spartaria. Una aproximación a su estudio, by José G. Morote Barbera.

- Historia de la Hispania romana, by Pedro Barceló & Juan José Ferrer Maestro (2022, first edition 2007).

- Historiae II, 54, by Sallust.

- Histories against the Pagans, book 5.23, by Orosius.

- L’Albufera de València. Comercio y frecuentación ultramarina entre los siglos VI y II a.C. by José Pérez Ballester (in “SAGVNTVM: Papeles del laboratorio de arqueología de Valencia, Extra-17. El sucronensis sinus en época ibérica,” edited by Carmen Aranegui Gascó).

- L’Almoina Archaeological Centre.

- La destrucción de Valentia por Pompeyo (75 a.C.), by Llorenç Alapont Martín, Matías Calvo Gálvez & Albert Ribera i Lacomba.

- Life of Pompey, 19, by Plutarch.

- Life of Sertorius, 19, by Plutarch.

- The Civil Wars, book 1.110, by Appian of Alexandria.

- The Sons of Remus: Identity in Roman Gaul and Spain, by Andrew C. Johnston (2017).

- The substratum permanent structures of Roman Valencia, by Giancarlo Cataldi & Vicente Mas Llorens.

Footnotes

- Note that the source’s “ten thousand soldiers” might truly mean that 10.000 soldiers got killed in the fight, but that it could also be a figure of speech. The original Greek uses the word “myriad” which technically means 10.000, but was also often used figuratively. The source material of Plutarch’s Life of Pompey might thus be more popularly translated “…near Valentia [Pompey] conquered Herennius and Perpenna, men of military experience among the refugees with Sertorius, and generals under him, and slew [a ton] of their men.” ↩︎

- If you want to read the specifics, you can find descriptions, photos of the original findings, and visual recreations in the article “La destrucción de Valentia por Pompeyo (75 a.C.)” by Llorenç Alapont Martín, Matías Calvo Gálvez, and Albert Ribera i Lacomba (in Spanish). ↩︎