It is the year 138 BCE. Rome is a rising power, but still far from achieving the enormous size and shape we all recognise on a map. The Iberian Peninsula is not yet fully under Roman control. In fact, Rome has been struggling to subdue the Hispanic tribes for about eighty years. Livy, one of the most famous Roman historians, describes the wars and chaos in Hispania, and right in the middle of it all, writes about the foundation of Valencia:

In Hispania, consul Junius Brutus gave land and a town, called Valentia, to those who had fought under Viriatus.

Livy, Periochae 55.4

More than 2160 years after the events Livy is talking about, this single line still causes debate among historians. Because something does not add up. It is time to unravel this story!

Who founded Valencia?

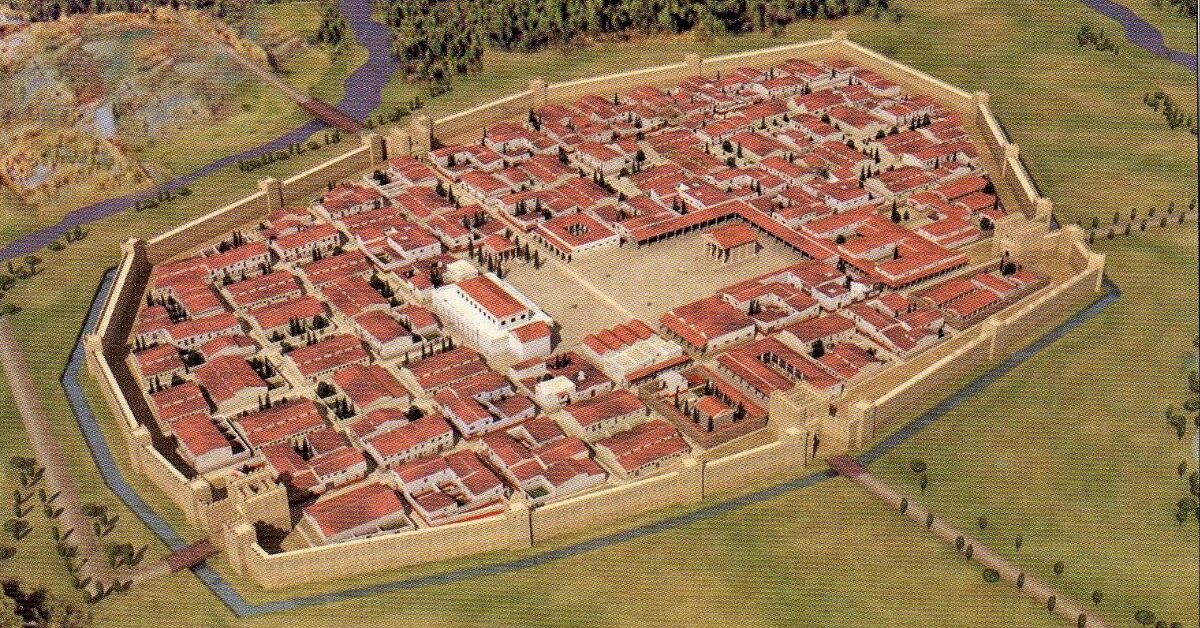

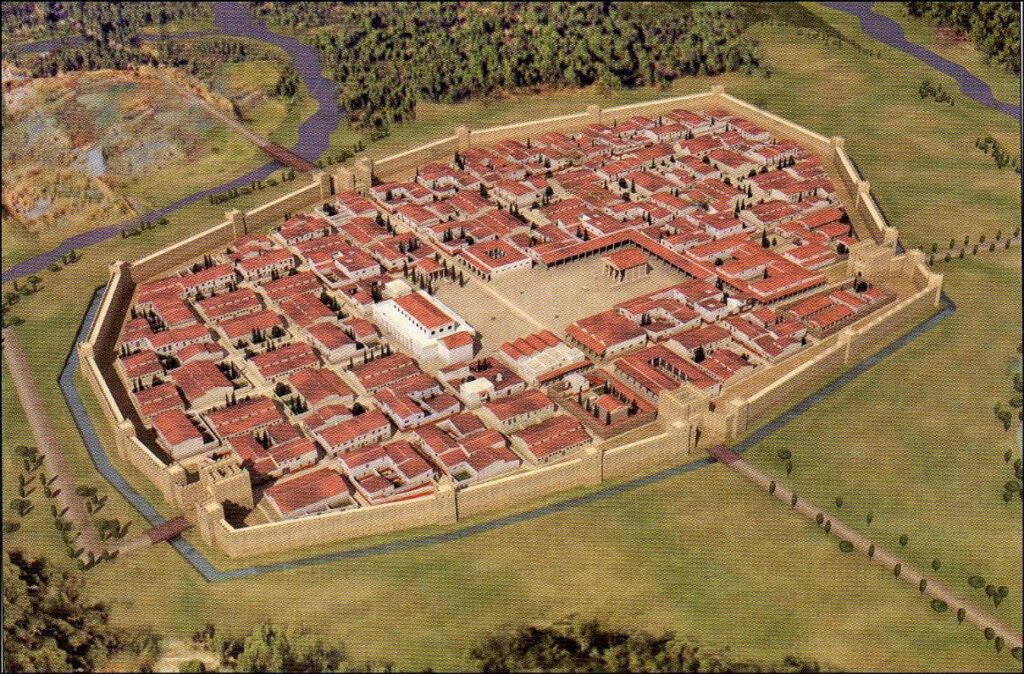

If you ask any guide in Valencia who founded the city, the answer is clear: the Romans did! In 138 BCE one of the two Roman consuls, the most senior magistrates of the Republic, was Decimus Junius Brutus. He ordered a new town to be built on a strategic spot, right where the Via Heraklea1, an important road following the Spanish coast from Tarragona to Cartagena, crossed the river Turia. The town was located halfway between these two cities, about 250 kilometres each way. As such, it protected the road and controlled trade going inland by river, and seawards to the Roman homeland.

So that sounds like sound decision-making by consul Brutus. And so far, all historians and archaeologists agree on the facts. But Livy not only said who gave the order for the foundation of Valencia, but also for whom this new town was meant. And there the waters get murkier, because who exactly are “those who had fought under Viriatus”?

Expand: Was Valencia built on an island?

Often books, websites, and other media discussing Valentia mention that the town was built on a fluvial island in the middle of the Tyris (later Turia) river. This has been debunked. In fact the town was constructed on a small hill just south of the river, overlooking the surrounding countryside. You can still notice this height difference in streets like Carrer del Palau. On some occasions, for example after heavy rainfall, the river would flood areas to the south of that hill, such as current Plaça del Mercat and Plaça de l’Ajuntament, leaving the town temporarily shut in by the water. However, it was never a true island.

Who settled Valencia?

Viriatus was not a friend of Rome. Far from it, in fact. One of the Hispanic tribes which for decades refused to submit to Roman rule were the Lusitanians. They lived in what is nowadays Portugal and western Spain, and from there they often raided Roman territories. For over sixty years they were a thorn in the side of the Romans, and this thorn inched deeper beginning in 147 BCE.

At that time, the Lusitanians united under a new leader, Viriatus, who very effectively lead the resistance against the Roman invaders. However, the Roman reaction to his resistance was so barbaric, that in 139 BCE some Lusitanians betrayed Viriatus and murdered him in an attempt to end the war. A short while after, the Lusitanians finally submitted to the Romans.

So Viriatus made life impossible for the Romans for close to a decade, was murdered, and then the next year the Roman leadership gave a whole town and territory to Viriatus’ people? And before you ask: no, this was not a way of rewarding the men who just killed Viriatus. The Romans outright denied any payment to his killers because they considered that traitors should never be rewarded. No, something else must have been going on.

There are two interpretations of Livy’s claim that Valencia was given to “those who had fought under Viriatus.” The first interpretation is that Livy described a smart move by the Romans to neutralise the threat of a persistent enemy. The other interpretation simply assumes that Livy made a mistake.

The foundation of Valencia as smart problem-solving

If we take Livy’s word for granted, the Romans were addressing the core problem that the Lusitanians faced. Lusitania had few natural resources and fertile lands. Because of that, its people often raided neighbouring (read: Roman) territories. There they could steal food, or loot which could be traded for food. Of course, this inconvenienced the Romans enormously. At several points the Romans offered to resettle Lusitanian tribes to other areas of Hispania. The condition: submission to Roman rule and disarmament.2

Offering such a deal, the Romans tackled three problems at once. First, resettled in more fertile lands, the Lusitanians would no longer have the necessity to go raiding, because food would be readily available. Second, without weapons, the Lusitanians no longer posed a threat, even if they felt like raiding anyway. And finally, the Romans could use these people to settle lands which so far had gone underdeveloped, and thus contribute to the Roman treasury!

All (ancient) historians agree!

Historians who emphasise this, argue that Livy simply described one of these deals. A group which surrendered to the Romans after Viriatus was murdered, took the deal to be resettled and got “land and a town, called Valentia” from consul Brutus. Two other sources describing the end of the Lusitanian War support this view, both Greek historians who lived in the Roman empire:

After having caused panic among the troops of Tantalus, successor of Viriatus, and having imposed a treaty to his liking on them, [the Roman consul] gave them a territory and a city to live in.

Diodorus Siculus 33, 1, 4

Caepio [Brutus’ predecessor as consul] stripped them of all their weapons and granted them enough land so that they would not have to practice pillage due to lack of resources.

Appian of Alexandria, The Wars in Spain 75

The latter of these writers, Appian, provided a bit more context for this particular event. According to him, directly after Viriatus’ death, the Lusitanians elected Tantalus as their new leader. Tantalus immediately decided to drive his army across the Iberian Peninsula and attack Cartagena, one of the most important Roman towns in Hispania at the time. However, the attack failed and Tantalus had to retreat. Consul Caepio pursued his army so tenaciously that finally the exhausted Lusitanians gave up. They surrendered “on condition that they should be treated as subjects.” Appian claimed that this was the reason for their peaceful resettlement. And it would make perfect sense to settle these people on the spot where Valencia was built. After all, they constructed the town right on the main road leading away from Cartagena, where Tantalus’ surrendered army would have been at that moment!

So, at least three ancient sources, not too far removed in time from the actual events, corroborate each other. But now, let us turn to modern historians, and see why some of them disagree with their ancient colleagues.

Oh Livy, why do you confound us with mistakes?!

Because if it were that simple, I would not be writing this. To many modern historians it seems unlikely that this new town Brutus is founding would be meant for a tribe of former enemies. Rather they claim that veteran soldiers who had fought for the Romans against Viriatus settled Valentia. This has to do with the fact that, besides Livy’s short line, there is no further evidence to prove that Lusitanians actually lived here. So, what evidence do we have?

What is in a name?

In the first place, we have the name of our new town to consider: Valentia Edetanorum. The add-on ‘Edetanorum’ is simply a reference to the area that Valentia is founded in; a region known at the time as Edeta. Because multiple Valentia’s existed in those days, this indicated the location this specific Valentia could be found in.

But the name ‘Valentia’ itself is relevant to our discussion. The most common opinion is that valentia, Latin for vigour or strength, was an honorary title given to the soldiers who settled here. Supposedly they had shown this particular quality in the Lusitanian War. The soldiers gave their ‘nickname’ to their new home-town, so people would know who lived there. Another possibility is that the Romans often named new colonies after certain virtues. Whatever the case, the important part here is that it is a name given according to Roman custom, which would be unexpected for a town meant for Lusitanian people.

What is in the ground?

However, our evidence grows stronger in another department: archaeology. Various sites throughout the city have been dug up, and with every dig one thing has stood out: Valentia had an undeniably Roman design. From individual buildings to the lay-out of the streets, everything identified so far has been distinctly Roman (or at least Italian) in nature. Not a single structure has shown the characteristics of Lusitanian constructions or those of any other indigenous group. It seems that all the physical evidence shows a town designed according to Roman or Italian culture.3 Again, it seems strange that an Iberian tribe would suddenly, without any transition period, fully adopt the infrastructure and architecture of a foreign group that until literally a moment ago had been its sworn enemy. And in contrast to the written word, stones rarely lie…

What is in your pockets?

That pattern continues when you analyse the coins and the everyday objects that have been found in and around Valencia. Found coins are from either the Italian peninsula or Valencia itself, as it quite early on had its own mint. That last piece of information also indicates that Valencia had a relatively high social standing within Hispania. Only a select few important towns were allowed to mint coins under the Roman republic!

In the archaeological digs many pots, pans and other everyday objects were found as well. These were mostly Italian in nature, significantly often from Campania (the region of Capua, Naples, and Pompeii). This might indicate that the Roman veterans who settled Valentia were originally from Campania, or alternatively that Valentia functioned as a transit port for Campanian products. Or it could have been both, with Campanian settlers in Valentia setting up trade routes with their relatives across the Mediterranean Sea.

Just another Roman standard operating procedure

Creating a colony by settling veterans from the Roman army was a common occurrence in the Roman Republic. Often the areas it had conquered remained restless and insurrections happened regularly, especially in Hispania. Building a stronghold and manning it with a group of veterans who had proven their loyalty and had fighting experience, that was just good strategy!

Valentia’s status as a colony meant that it functioned as an extension of the Roman homeland. Because of that, free inhabitants had certain legal rights and thus a higher status than residents from local settlements (though not full Roman citizen status).4 This would have been much more likely to be granted if the first Valencians actually originated from one of Rome’s allied communities, for example Campania.

Conclusion

If we believe this point of view, then of course Livy was wrong about the foundation of Valencia. He should not have written that “consul Junius Brutus gave land and a town, called Valentia, to those who had fought under Viriatus,” but that he gave it “to those who had fought against Viriatus.” That might have been a simple writing error; he might have just chosen the wrong word while being distracted. Or otherwise, he might have known about the Roman practice of disarming troublesome tribes and giving them land to live peacefully, and have assumed that this happened in Valencia as well, especially because both Appian of Alexandria and Diodorus Siculus describe something similar (though without explicitly mentioning Valentia).

Unfortunately, about 2000 years divide us from Livy, Appian and Diodorus, and all that remains to us are partial literary evidence that tells us one story, and archaeological finds that tell us another. And as mentioned before: in contrast to the written word, stones rarely lie. The most likely candidate for the truth seems to me that Valencia was founded by and for Roman veterans.

Whatever the case, Valencia now exists! We have a new town, set up by Roman initiative and according to Roman custom. It is strategically well-placed to control the surrounding area and will quickly grow into a prosperous economical centre for the region. The foundations are laid for a prosperous future. What could possibly go wrong?

In our next story, Valentia burns and is wiped off the map…

Sources

- Appian’s Roman History (translated by J.D. Denniston), by Appian of Alexandria.

- Historia de la Hispania romana, by Pedro Barceló & Juan José Ferrer Maestro (2022, first edition 2007).

- Inscripcions romanes del País Valencià, V (Valentia i el seu territori), by Josep Corell Vicent. (2009).

- Periochae, by Livy.

- The Roman foundation of Valencia and the town in the 2nd-1st c. B.C., by Albert Ribera i Lacomba (2006, chapter from Early Roman towns in Hispania Tarraconensis).

- The Sons of Remus: Identity in Roman Gaul and Spain, by Andrew C. Johnston (2017).

- The substratum permanent structures of Roman Valencia, by Giancarlo Cataldi & Vicente Mas Llorens.

Footnotes

- This road will later be included in the Via Augusta, the most important Roman highway in Hispania and its main connection with Rome itself. ↩︎

- It is important to mention that the Romans would sometimes make this offer as a ruse. In fact, Viriatus was a survivor of one of the times that the Romans offered the Lusitanians a deal of this kind, and then after disarming the group, massacred most of them anyway. ↩︎

- New Roman towns such as Valentia were designed to be ideally distributed. The town was built around the crossing of a north-south road (cardo maximus, nowadays Carrer del Salvador) and an east-west road (decumanus maximus, nowadays Carrer dels Cavallers), and a large central square (Forum Romanum, nowadays Plaça de la Mare de Deu/Plaza de la Virgen). You can find remnants of the original roads in L’Almoina Archaeological Centre in Valencia. ↩︎

- Roman society was very hierarchical: citizens of Rome itself enjoyed full citizen rights; citizens of Italian cities allied with Rome enjoyed less expansive, but still reasonable rights; people in the subjugated territories had only basic rights. As a so-called ‘Latin colony’ Valentia fell under the second category, and so most probably its citizens came not from Rome itself, but from the Italian region of Campania. ↩︎